Interesting times, no? We live in interesting times. Oh ho ho the times they are interesting. By that, of course, I mean that I am very bored, but at the same time so anxious I am giving myself headaches. Pandemics are not fun! Staying in your house is not fun! Worrying that people are going to die is not fun! Watching governments debate whether rich people’s wealth is more important than people dying is not fun!

This is not as bad as living through the Black Death, or the plague generally.

And … you know that. You fundamentally understand that this is true. But it is also true that it is coming up over and over again right now as we all struggle to connect to something historical in the midst of a difficult time.

Now some of you may be wondering why I have deliniated between the Black Death and the plague up there. Well, that’s because the Black Death was an outbreak of bubonic plague, but not all bubonic plagues are the Black Death. (All squares are rectangles, not all rectangles are squares, etc etc etc.)

K, so TF does that mean? Wellllllll the Black Death was, of course, an outbreak of the bubonic plague, otherwise known as Yersinia pestis. The thing about the bubonic plague is that it is a real one and it has been around the joint for a long damn time. The first European incursion of Yersinia pestis can be linked, for example to the early medieval period, when historians refer to it as the Justinian Plague. This little episode lasted from 541-542 and it was primarily felt in the Eastern Roman Empire (AKA Byzantium for the anachronistic crowd), especially in the capital Constantinople. It also killed a lot of people over in the Sassanian Empire, which we now know as Iran. When all was said and done after several recurrences, some historians have estimated that the Justinian plague killed about 25 – 100 million people, or about half the population of Europe. We are currently reassessing this as some historians have pointed out that these estimated may be based on traumatised people being extra, given that we don’t have the physical evidence to back it up. Either way, it was some real shit. It was not, however the Black Death.

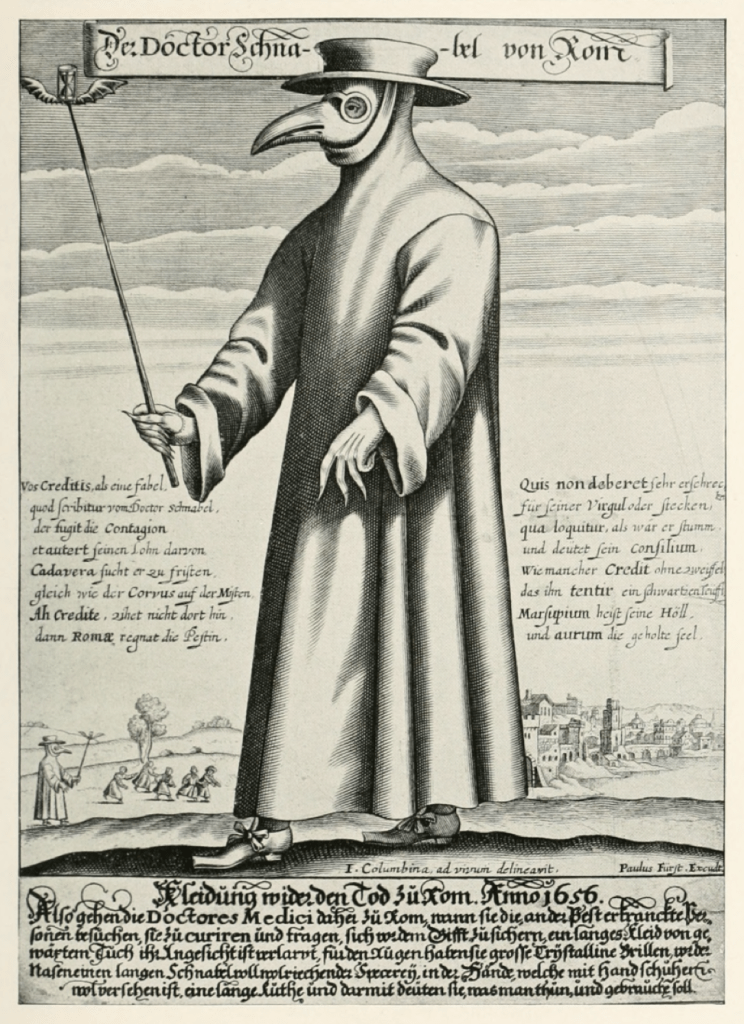

Similarly, the piece of plague memorabilia that likely springs to mind when you think “plague”, aka plague doctor masks, are also not about the Black Death. Instead, they are linked to an outbreak of Yersinia pestis from the seventeenth century. Which means – and I cannot stress this enough – THEY ARE EARLY MODERN, AND NOT MEDIEVAL.

Paul Fürst, engraving, c. 1721, of a plague doctor of Marseilles (introduced as ‘Dr Beaky of Rome). I cannot tell you strongly enough how not medieval this is.

More specifically, they are linked to physicians in what is now France and Italy. A French medical Doctor Charles de Lorme helped to conjure up the beaked mask, the beak of which was filled with aromatic herbs to protect against miasma – or ill smells that were thought to make people ill. It also involved spectacles to protect the eyes and waxed leather robes that were thought to act not unlike armour. Lorme described his mask as having a “nose half a foot long, shaped like a beak, filled with perfume with only two holes, one on each side near the nostrils, but that can suffice to breathe and to carry along with the air one breathes the impression of the drugs enclosed further along in the beak.”[1]

This get up would remain popular with doctors working against the plague up into the eighteenth century, as they fought what historians refer to as the “Great Plagues”: a series of out breaks of Yersinia pestis including the Great Plague of Seville, the Great Plague of London, the Great Plague of Vienna, and the Great Plague of Marseille. This is just to name some of the major great plague hits but – crucially – these were not the Black Death.

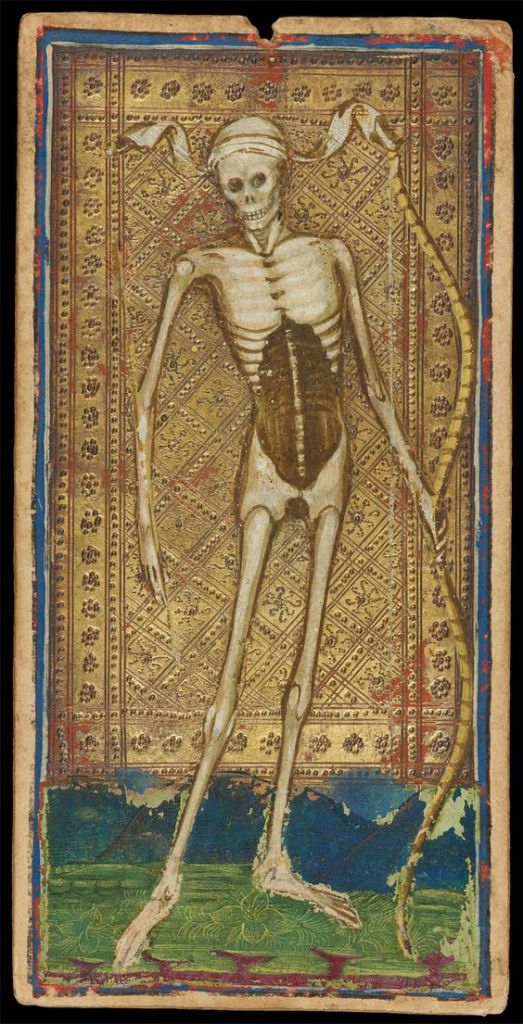

This is because the Black Death is – specifically – the occurrence of Yersinia pestis linked to the fourteenth century. For those of you who like specifics, it started in Central Asia, and more specifically in what is now Kyrgyzstan around 1332 or so. A TL/DR of how Yersinia pestis managed to make the great leap into humans was that it had been out on the steppes of central Asia hanging out in the guts of fleas. The fleas lived in marmot colonies. With increasing trade across the Silk Road (because the fourteenth century fucking ruled and people were getting their spices on after a period of instability after the Mongol conquests. Shout out to my crew.) these marmots came into contact with the animals who were also caravanning about the joint. I mean horses, camels, and also humans but yeah rats. (It is important to me that we acknowledge that the problem here was fleas and not rats. #RatsDidNothingWrong) The fleas bit people up and travelled in some style east into India and China and west into Europe and the Middle East. It made it to Europe by 1347 and had more or less petered out after 1351, though it never really went away again, as the seventeenth century plagues illustrate.

It was, and is a fucking terrible and gruesome disease. The poet Boccaccio wrote of it in the Decameron:

“In men and women alike it first betrayed itself by the emergence of certain tumours in the groin or armpits, some of which grew as large as a common apple, others as an egg … From the two said parts of the body this deadly gavocciolo soon began to propagate and spread itself in all directions indifferently; after which the form of the malady began to change, black spots or livid making their appearance in many cases on the arm or the thigh or elsewhere, now few and large, now minute and numerous. As the gavocciolo had been and still was an infallible token of approaching death, such also were these spots on whomsoever they showed themselves.”[2]

While Bocaccio isn’t entirely correct here, in that it was theoretically possible to maybe survive if your buboes discharged on their own, (good luck champ!) – yeah most people who got this died. All in all it took down a quarter of the world’s population at the time, but that is an overall estimate. In some places the death toll was worse. We estimate that the population of Paris fucking halved. In 1338 Florence had about 120,000 inhabitants. When the Black Death abated 50,000 were left. In Bremen about sixty percent of the population died. In quiet backwaters like England entire villages were lost as those who survived couldn’t keep them running and moved elsewhere.

My point is this was a catastrophe that we simply cannot comprehend. This is not only because the mortality that we are seeing with Covid 19, which is already horrifying and numbing, is much smaller – but also you know why it is happening. You understand germ theory. You know the name of the fucking virus. All the people who died of the plague – in the Black Death or not – knew it was a sickness, but that is all that they knew.

The reason that the seventeenth-century plague doctors wore them beaky masks was because they, like many medieval physicians before them, had a best guess for what was causing the plague – miasma. Miasma theory, more or less, was the idea that bad smells or noxious air could cause diseases. It was the prevailing medical theory (in conjunction with humoral theory, which we have talked about before) up until the second half of the nineteenth century.

Even if you were pretty sure you had it nailed on miasma theory causing plague though, that doesn’t necessarily explain where said miasma came from. There were some competing ideas on this one. Some argued that the noxious air had come out of the earth’s crust during a major earthquake in Friuli (in what is now Italy) in 1348. It was a 6.9 on the Richter scale and was so strong it was felt as far away as Bohemia and the German lands. Such medical luminaries as Avicenna had argued that earthquakes could release gases which would petrify men or turn them to pillars of salt.[3] Why not gases that caused plague?

The Paris medical faculty, meanwhile argued that the gases had been caused by a “major conjunction of three planets in aquarius…[where] Jupiter, being wet and hot, draws up evil vapours from the earth and Mars, because it is immoderately hot and dry, then ignites the vapours, and as a result there were lightnings, sparks, noxious vapours and fires throughout the air. … Mars was also looking upon Jupiter with a hostile aspect, that is to say quartile, and that caused an evil disposition or quality in the air, harmful and hateful to our nature.”[4]

Also they were pretty sure that a corruption of food made stuff gross as well, but the major thing was the air corruption caused by the planets.

Now you, standing on the shoulders of giants, and having been told what a germ is from your childhood may laugh at this. But you have not been taught astronomy from an early age and been taught that the planets really do influence what happens with life on earth.

Moreover, you can go ahead and find the explanations for how the miasma occurred weird, but the thing about miasma theory itself is that it kinda seemed realistic based on actual observation.

Wash people up so they smell better? Incidences of disease go down a bit. Improve sanitation? Same deal. That is how you find yourself walking around with a bird mask stuffed full of aromatic herbs to keep yourself safe from plague. If you can’t smell the bad air, then you might be safe.

Sadly though, you would not, in fact be safe with a mask. Not in the early modern period when they were worn. Not if you sent the masks back to the medieval period by time travel just to prove some sort of long-game point to me. (I see you haters. I see you.) Not at all. So you would die. And your loved ones would die. And so many people would die it would feel like the end of the world.

This brings me to another reason why I think we bring up the Black Death in times like these. Because we know, deep down, that it was one of the most horrible things that humanity ever went through. You probably knew the figures about death off the top of your head! The idea of plague doctors lives in our cultural imagination even if people are misidentifying a modern phenomenon as a medieval one. Our go-to cultural reference for pandemic is the Black Death because it was so so bad … but humanity made it through.

It is comforting at times when stuff is scary and our general way of life is breaking down around us to know that worse things happened before and yet society continued on. Our medieval ancestors might have thought it was the end of the line, but it wasn’t. And in our heart of hearts we know we are better off. When you are facing something really scary down, it can be helpful to reflect on when times were worse. I mean, sure, we might not have enough ventilators, and our doctors don’t have adequate PPE, but it’s not bird masks and sweet orange peel, you know?

I understand why people want to reflect on the plague right now. I really really do. But let’s take comfort in the fact that as scary as this is, it is not the Black Death, and it’s not even the subsequent plagues.

They didn’t know what caused their pandemic, we do. They didn’t have medical interventions, we do. Are we prepared? Um, no. But we have models of other countries who have beat this very infection and it is to be hoped that at some point our leaders will be forced to try that.

In the meantime, I grant you the small joy of correcting people about plague masks. We all need new hobbies.

[1] Vidal, Pierre; Tibayrenc, Myrtille; Gonzalez, Jean-Paul (2007). “Chapter 40: Infectious disease and arts”. In Tibayrenc, Michel (ed.). Encyclopedia of Infectious Diseases: Modern Methodologies. John Wiley & Sons. p. 680.

[2] Boccaccio, Decameron, trans. M. Rigg (London: David Campbell, 1921), Vol. 1, pp. 5-11.

[3] Konrad von Megenberg, Buch der Natur, 2, 33.

[4]“The Report of the Paris Medical Faculty, October 1348”, https://sites.uwm.edu/carlin/the-report-of-the-paris-medical-faculty-october-1348/.

If you enjoyed this, please consider contributing to my patreon. If not, that is chill too!

For more on medieval medicine and the Black Death, see:

On masculinity and disease

On collapsing time, or, not everyone will be taken into the future

Plague Police roundup, or, I am tired, and you people give me no peace

Chatting about plague for HistFest

On the plague, sex, and rebellion

On Medical Milestones, Being Racist, and Textbooks, Part I

On Medical Milestones, the Myth of Progress, and Textbooks, Part II

On medieval healthcare and American barbarism

Thank you Eleanor. Informed, spirited, funny and optimistic.

LikeLiked by 7 people

So glad you found it helpful Sascha.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Lovely article, I learned a lot! Thank you for writing and sharing.

LikeLiked by 7 people

Yersinia pestis is the organism that causes the plague. Just a note because I think that can get confusing when discussing a disease versus the organism that causes the disease. Just a technicality but it’s important to distinguish right now – especially in an article re:infectious diseases.

LikeLiked by 5 people

I think I made that clear, no?

LikeLiked by 2 people

First off, thank you for writing this. It was very informative.

I just wanted to add that I didn’t realize from the article that Yersinia pestis was the name of the organism rather than the disease. After reading the original comment, I went back and reread, but it still wasn’t clear to me.

Rather, you introduce Y. pestis by saying this:

“Wellllllll the Black Death was, of course, an outbreak of the bubonic plague, otherwise known as Yersinia pestis.”

LikeLiked by 1 person

Gotcha!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Whoa. Important. How so?

LikeLiked by 1 person

I had never questioned the true origin of plague masks. Thanks for the education, and also thanks for the uplifting ending. Definitely made me feel a little better about out current situation.

LikeLiked by 6 people

So glad you found it helpful!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Loved reading this! I teach this to kids and I just learned a ton that I’ll pass on to my kids!

LikeLiked by 6 people

This is one of the best things I’ve read on wordpress! Great article!

LikeLiked by 6 people

Wow what a post, I learnt a lot, keep up the good work

LikeLiked by 6 people

I learned a lot! An interesting take on relevant topics.

LikeLiked by 4 people

Thank you for sharing your thought. I hope everyone in your family is safe in this time of pandemic. Now that everyone must stay home, I was inspired of starting this blog. I am hoping for your support by visiting my blog and leaving your footprint via comment. God bless always.

LikeLiked by 4 people

What you said about how we’re better off in this age facing this pandemic is very true. I could only imagin how people in the 14th and 17th century carried on fighting against a disease they know nothing about.

I learnt a lot from this article.

LikeLiked by 5 people

Absolutely amazing!

LikeLiked by 5 people

Thank you Dr. Janega! I appreciate the history lessons, explanations and more so your authentic spunky voice.

LikeLiked by 5 people

Great article! I loved reading it! I listened to the episodes of the podcast ‘Our fake History’ about the Black Plague yesterday, you might like it as well! He didn’t know Corona was going to happen back then, so it’s pretty strange to hear him talk about the differences and similarities between that and this pandemic, without him knowing.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I loved this! Well written and entertaining. 🙂 I’m a writer who has been researching the 1720 Marseille plague for the last few years for my novel. We are so lucky to know what we are facing with this pandemic and have health systems.

LikeLiked by 4 people

Oh completely. And now THAT was a scary pandemic.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you for sharing. It is informative.

LikeLiked by 2 people

We learn everyday.

LikeLiked by 2 people

This was beautifully explained! 🙂 wonderful blog

LikeLiked by 1 person

That is so kind of you to say. I am so glad I enjoyed it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great post! I’m new to blogging community, it’s so good to come across such amazing stuffs!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Amazing article! Very informative.

LikeLiked by 2 people

This was a really entertaining read, thank you!

LikeLiked by 1 person

So glad you enjoyed it! Thanks so much for saying so.

LikeLike

Loved reading it. 😍 I enjoyed. it!

LikeLiked by 2 people

I freaking loved this! I learned quite a bit and it was very amusing to read haha

LikeLiked by 1 person

This is a superb article and so buoyantly written; I love your style! Makes me actually want to read a bit more on this topic. I don’t suppose you have any recommendations?

LikeLiked by 1 person

I absolutely do! I like Norman F. Cantor’s In the Wake of the Plague, for discussions of how things change. If you want to read primary sources from the Black Death, try Rosemary Horrox, The Black Death. John Abeth’s The Black Death 1348-1350 is a good starting place and has a short history with some documents. Happy reading!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much for this.

LikeLike

Always happy to help!

LikeLiked by 1 person

The article was very interesting and those images were a fantastic addition. Thanks!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Dr. Janega, that is the best article on any topic I’ve read in a long time. It was educational, entertaining, relevant, and hilarious. Fantastic work. I’m a fan.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That is extremely kind of you to say. So glad you enjoyed it!

LikeLike

As a rat owner, I thank you for the hash tag rats did nothing wrong. My babies get enough hate for no other reason then they are rats.

LikeLiked by 1 person

My love to them. I like how smart they are, and also they tiny feets.

LikeLike

Great article which puts things in perspective.

LikeLiked by 1 person

A very informative read and i wish historians played a more active role in the mainstream discussions.

In the concluding paragraph, you said that we know what the source of this pandemic is. But I doubt that is the case given how there has been a lot of misinformation claiming bat-eating for being the root cause of this outbreak in the earliest stages of this outbreak. Later on, some scientists opined that it might have made a cross-species jump from pangolins but that seems to remain hypothetical. Scientists have also began pointing out that deforestation is going to lead to more spill over of viruses in wildlife, making cross-species jumps like this more often.

As a nobody and just another layman, I think it is safe to say we aren’t that much different from the people in the past who trusted in their knowledge of astronomy. And perhaps one day in the future, people would look back at this point in history and frown upon us or chuckle at some of our blunders.

LikeLiked by 1 person

A good point. I suppose I meant more that we were aware that it was a virus. Certainly we are at as much of a loss as any medieval person about its origin.

LikeLike

Did the incidences of major wars increase or decrease during the Black Plague years? It seems like there would have been many territories so decimated that they would have been easy conquests, but raising and marching an army would have been exceedingly difficult.

LikeLiked by 1 person

They go down during the pandemic itself because there aren’t enough people to fight. We see, for example, the Hundred Years War come to a halt at this time because you can’t muster an army.

LikeLike

Wow. I thought I was good at writing – then I read this post! Brilliant article – one of the best I have come across.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You absolute sweetheart.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The juxtaposition of headaches and boredom with something as horrific as The black death is surprising.

Interesting that it also jumped from animals and followed a similar route as Covid.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Bravo! I learned something new in this article about those long nose masked and I know you did your research. I read the whole article and felt your words were real. Thanks for the good read!

LikeLiked by 3 people

Sorry if you get this question all. the. time., but what are your thoughts on the alternate theories of the Black Death not being caused by y. pestis since (among other evidence) it traveled much faster than the modern outbreaks of bubonic plague? I think a hemorrhagic virus is seen as the most likely suspect for those who don’t think it was caused by y. pestis.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I just don’t really care, to be honest. What the actual germs are makes very little difference. What matters is that everyone died and it was super scary. Ultimately the germs that did it don’t make that much of a difference.

Also for what it’s worth any actual analysis of bones comes back as y. pestis, so I mean the theories are fun, but they don’t make much of a difference to social historians.

LikeLike

Lovely write up ♥️

LikeLiked by 1 person

This was a very good read. I appreciated your shout out to Giovanni Boccaccio, he was awesome. The Decameron is an amazing read! Humanity will survive and thrive after this pandemic is over.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Fascinating! I love reading about how the contemporary people would have interpreted all of this. A Very Fictional Account that seemed (to me) to capture that bleak sense of impending disaster during the Black Death was Connie Willis’s Doomsday Book. I highly recommend it!

LikeLike

Oh thank you for this recommendation?

LikeLike

quite entertaining analysis …

LikeLike