You will no doubt be unsurprised to learn that last night I went to the pub. There are several reasons for this, chief among them being that in the discomfort of summer, going to the pub is quite the best thing you can do with your time in London. Also, it is the best thing to do with your time when it is cold in the winter. Also, in autumn and spring. Anyway, the point is that conditions have been so miserable here that it has sort of been impossible to do anything except drink beer as a form of recreation, so I have been doing that.

This state of affairs made me think about medieval people, as I do, for a couple of reasons. One, I am very happy that I am not doing manual labour in a field bringing in the hay right now, as is usual for August for the majority of medieval Europeans. I cannot imagine having to do that now that we have 34 degree days for some reason. No thank you. Second, my sitting around enjoying many delicious beers made me think about how chicks rock.

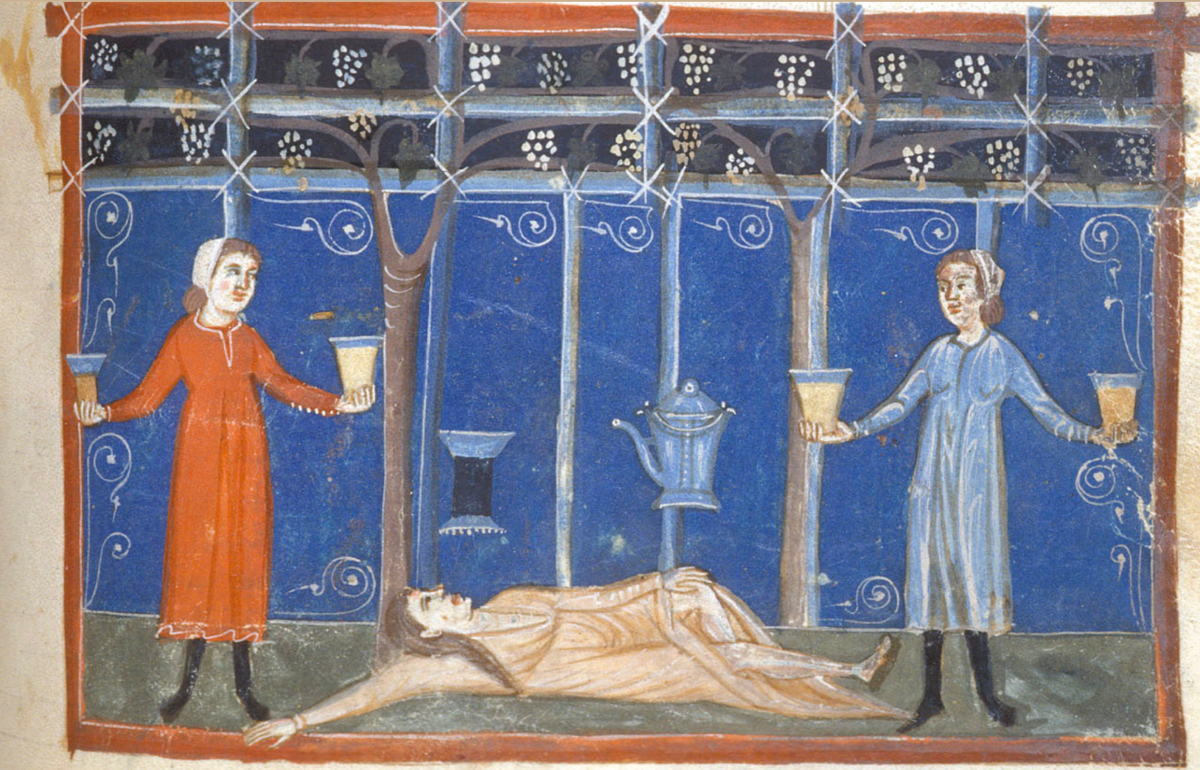

I say this because, as you may or may not know, one of the major jobs for women in medieval Europe was brewing. Brewing wasn’t necessarily always thought of as women’s work, but it was a type of employment where women were at least as well represented as men. Women got into the beer game because you needed so much ale just to live a nice life as a peasant that a lot of people made it at home. In particular what people wanted was small, or low alcohol, beer. The tenth-century text, Ælfric’s Colloquy, which is a series of imagined conversations between a teacher and his students speaks to the necessity of having beer around the place. One young man is heard to remark, “I drink ale, usually, if I drink at all, and water if I have no ale. … I am not rich enough to be able to buy myself wine: Wine is not a drink for boys or fools but for old men and wise men.”[1]

Interest in and demand for ale and beer is well recorded enough that by the eleventh century it was being made on a large enough scale in brewing centres. By the thirteenth century, places such as České Budějovice, which eventually graced the world with the original (and very good) Budweiser, were making beer that was so delicious it was being exported to Bavaria.[2] (The American company stole the name, used it to make abysmal beer, and then sued the original makers of the beer so now they can’t call it that. You’ll see it marketed instead as Budvar. Budvar is state owned, and can only be brewed in České Budějovice so if you see it, it is reliably good. Treat yourself and support the Czech people)

Now the fact that people were on the ale day and night is sometimes used to prop up an old myth that people drank ale because water was unsafe to drink in the medieval period. No. The majority of people lived in the countryside. I know you get tired of me telling you that but it bears repeating. So they actually had access to pretty good water. Probably better than we do now in England because water is privatised and firms like Thames Water and Southern Water keep just dumping untreated sewage into it because they don’t want to pay to dispose of it correctly. ANYWAY, the point is medieval people had safe water. People were drinking beer because farm work is really really hard and small beer and ale were sort of like medieval protein shakes or energy drinks. They were used to add additional calories to people’s diets in a delicious way. (So….maybe not like protein shakes or energy drinks, I guess.) Now the thing about needing this much beer is that, sure, stuff like professionally made imported ales and beers existed, but mostly only rich people could afford that. The great majority of people (shout out peasants), especially in the earlier medieval period, made their own, or bought it from people nearby.

If you are enjoying this post, why not support the blog by subscribing to the Patreon, from as little as £ 1 per month? It keeps the blog going, and you also get extra content. If not, that is chill too.

There is also a distinction to be made here about what they were brewing. Ale was most common for the majority of the medieval period because it is brewed mostly from barley and for flavouring uses something called ‘gruit’. Gruit is a mixture of whatever local herbs are lying around that can be added during the brewing process. For something to be a beer it has to have hops in it. Hops first gained wider usage in Europe likely from the ninth century. We have records from the Abbot Adalhardus in the monastery of Corvey on the river Wiser in what is now Germany saying that Millers didn’t have to do the work of ordinary peasants, which included picking hopes in 822, which is how we know.[3]

Hops were used for flavouring beer, yes, but they also are preservative which keeps the drink from going off. So, if you are brewing ale, say in a place like England which didn’t really take to the whole hops thing until into the fifteenth-century, you need to constantly be brewing to ensure a steady supply. This meant that most people constantly had some ale on the go in their own homes, making brewing a very common cottage industry. Women were often in charge of brewing for their families, because it was considered on par with cooking. When they did this they could also brew more than the family would drink, allowing them to sell it and make some extra cash. This meant that brewing could be learned at home, and that women could become employed as brewers in larger commercial breweries.

As a result, we find records of women in brewing everywhere. We have records of women paying taxes on their gains from brewing, or registering with brewing standards commissions. Standards for commercially sold beer and ale were high, and these collectives kept good records. That means that we tend to hear a lot about women who were not, in fact, very good at it. The Durham Court Rolls from 1365, for example, tell us that “Agnes Postell” was fined “for bad ale, 12d.” while at the same time a certain “Alice de Belsais” was fined “for bad ale, and moreover because the ale which she sent to the Terrar was of no strength, which was proved in court, 2s.”[4]

Fines for bad beer and ale were often monetary, but in true medieval style they could also go so far as public shaming. In England, the cucking stool, which eventually would become the early modern period’s waterboarding implement of choice, the ducking stool, is first recorded in (surprise surprise) the Domesday book. It tells us that it was used specifically in Chester to punish people who sold bad ale or ale in incorrect measures. The punishment was that whoever (woman or man) was making bad beer would have to sit in a chair outside their home and have people come by to yell at them about how much it sucked. This is kind of funny, to me.

Later, the fourteenth-century Regiam Majestatem which collected Scottish laws, said that in the kingdom anyone who “makes evil ale, contrary to the use and health of the burgh and is convicted thereof shall pay … eight shillings or shall suffer the justice of the burgh, that is she shall be put upon the cuck-stule”.[5] You’ll note the “she” here, which shows us that people expected brewers to be women there. As a result, we can understand the cucking stool as a sort of gendered humiliation and indeed, by this time men largely didn’t face it as a punishment.

Another, and very sad, way that we can learn about women brewers is through accident records. One coroner’s roll from England records, for instance, that at “About nones on 2 Oct, 1270 Amice, daughter of Robert Belamy of Staploe, and Sibyl Bonchevaler were carrying a tub full of grout [gruit – the herb flavouring agent] between them in the brewhouse of Lady Juliana de Beauchamp in the hamlet of Staploe in Eaton Socon, intending to empty it into a boiling leaden vat, when Amice slipped and fell into the vat and the tub upon her. Sibyl immediately jumped towards her, dragged her from the vat and shouted; the household came and found her scalded almost to death. A chaplain came and Amice had the rites of the church and died by misadventure about prime the next day.”[6] This always makes me really sad and also freaks me out, and is a reminder that brewing – especially in commercial quantities – was a physically demanding and dangerous job. And women were oftentimes the ones specifically doing it.

You’ll also note here who the unfortunate Amice, and Sibyl were brewing for. They were employed by another woman, and a lady at that, Juliana de Beauchamp. Here we see how brewing was closely related to women across even the rigid hierarchical structures of the medieval period. Sure, Lady Juliana had hired women to take on the dangerous parts of the job. But the brewhouse is specifically listed as being hers, and the women as her employees. The Lady Juliana could therefore be seen as a brewer even if the working class were doing all the actual work (as per). Anyway, the point it girls do be brewing in the medieval period.

This may come as a surprise because today beer is often seen as a specifically masculine thing. Why is that? Well a lot of it has to do with the process of industrialisation. As beer making became increasingly professionalised, women were often moved out of it in favour of men. This is, sadly, a standard condition in our work forces. When men start doing a job that used to be low paid and usually done by women, the women are forced out and suddenly the pay jumps. Conversely if women start doing a job that was traditionally seen as masculine, say university teaching (*cough*) the pay suddenly drops.[7] Think about it like this – you know how “traditionally” women are the people who cook at home? Think about who makes up the majority of professional chefs. That but for beer.

A cool thing now is that women are back in brewing and I absolutely love to see it. If you’ve seen my tv show on beer, I actually had the pleasure of going to Wildcard Brewery here in London where their brewmaster Jaega Wisse made me a medieval ale. With gruit from local herbs and everything! And oh my god it was sooooooo good. The sad thing is it is never going to get to be sold because, you know, it doesn’t have hops in it so it only has a shelf life of like a week. I swear to you it took everything it had in me not to just snatch the container of beer there and run out with it.

Anyway, the point is if you feel the need to ask me, “Eleanor why are you spending all your free time drinking delicious beers in pubs this summer?” the answer is that I am actually partaking in an important and feminist tradition, thank you very much. Also it is very hot and I am lazy. Please make a note of it.

[1]Anne E. Watkins (trans.), Ælfric’s Colloquy: Translated from the Latin, http://www.kentarchaeology.ac/authors/016.pdf <Accessed 4 May 2021>, p. 13.[2] Roger Protz, “České Budějovice”, in, The Oxford Companion to Beer https://beerandbrewing.com/dictionary/jjPyHOOGtQ/ <Accessed 18 August 2022>.

[3] Ian Spencer Hornsey, A History of Beer and Brewing, (London: Royal Society of Chemistry, 2003), p. 305

[4] Emilie Amt, Women’s Lives in Medieval Europe: A Sourcebook, (London and New York: Routledge, 1993, p. 185.

[5] Llewellyn Jewitt, “A few notes on ducking stools”, Green Bag, 10, (1898), 522.

[6] Amt, Women’s Lives in Medieval Europe, p. 189.

[7] Asaf Levanon, Paula England, Paul Allison, Occupational Feminization and Pay: Assessing Causal Dynamics Using 1950–2000 U.S. Census Data, Social Forces, 88.2, December 2009, 865–891.

For more on why chicks rock, see:

On constructing the “ideal” woman

On Women and Work

On “the way of carnal lust”, Joan of Leeds, and the difficulty of clerical celibacy

Considering bad motherfuckers: Hildegard of Bingen and Janelle Monáe

On sex work and the concept of ‘rescue’

Support the blog by subscribing to the Patreon, from as little as £ 1 per month! It’s the cool thing to do!

My book, The Once And Future Sex: Going Medieval on Women’s Roles in Society, is out now.

© Eleanor Janega, 2024

Nice piece.

I seemed to remember different regarding the Budweiser name dispute and looked it up.

Wikipedia (I know, I am lazy too) states that by and large the Czecks have the rights in Europe, the Americans in NA and the rest of the world depends. If Airstrip One is Europe in this context I don’t know.

Anyway, as I saw once in Chester in a shop selling Budvar:”is to the American copy what Winston Churchill is to J. Danforth Quayle”.

LikeLike

Haha that makes me laugh. Thank you.

LikeLike

Yes indeedy! And Ceske Budejovice is worth a visit because it is terribly charming and Bohemian, and the freshest Budvar is there. One of my favourite summer pastimes, to be sure.

LikeLike

From the Wikipedia on ‘Alewives’:

“Non-married women, including single young women, widows, single mothers, concubines, and deserting or deserted wives, at times engaged in the brewing trade and made enough to support themselves independently.[34]”

I love this.

Also the Doom picture from St Thomas Becketts Church: That lady looks like she’s having a good time singing “Let it go” while her friend is trying to get her in the taxi, all the while the people in the queue to the club are pissing themselves laughing.

LikeLike

Apparently this long feminist tradition is coming to an end ?

https://www.theguardian.com/business/2022/aug/23/pubs-winter-energy-costs-soar

LikeLike

Reminds me of “Ask the Fellows Who Cut the Hay” George Evans 1956 book on folk and rural life as remembered by locals in his area. Memories stretching back to the late 1800s gathered, in Suffolk.

He gathered accounts of people talking about their home Ake making. That it would be weekly in some houses. A strong Ake made first, and a second batch made from the leftovers, small beer, low strength, for the children.

Often made by the women of the house, often tied into the weekly bread baking too.

And again, if memory serves, not because of water quality, but because you needed a calorific drink to carry you through the workday.

People might be paid in part for work in grain, specifically for bread and beer making.

Took hay on my farm with a scythe a few years ago in a heatwave. You cut in the early morning. Starting at fiveish. The dew on the grass makes it easier to cut, and you can’t work a scythe in afternoon heat the m a heatwave.

Hay turning happens during the day, which is tough, and again in the evening. But the tough work is done early, or late, if possible

I have cut and gathered in heatwave weather in the afternoon. Heat exhaustion hits after a out two hours when it becomes impossible to work

Thanks for the insights, detail, and historical context.

LikeLike