I had the singular pleasure of visiting with a bunch of my high school friends the other week, and one of them put me on to a podcast I had not heard about before Normal Gossip. She said it was something she thought I would like because, well, a thing about me is that I am interested in gossip – and I mean this in several ways.

Firstly, I mean I am interested in gossip as an academic concept. I like thinking about the way gossip is discussed in medieval sources. Secondly, I also like to think about how gossip is conceptualised by anthropologists, which is to say, I enjoy thinking about what it is that gossip does socially. Because it does a lot. Thirdly, I mean, look, I am a social historian. My job is to gossip about dead people. I sit around and read what they have written, or what was written about them. I rifle through records of their house contents to try to picture how they were living their lives. And I think about who is talking about them in order to try to put together an idea of what they were like – and then I tell people all about it. And like, let’s just be honest – My interest in this means that I am a professional gossip who writes on gossip as a concept and that’s cuz … I want to hear the gossip. You have some? Great, I want it. Is it about some people I have never even met and probably won’t ever meet? Even better. To me, every bit of anonymous gossip is my own private soap opera, and I simply love to hear it.

So today I thought we would have a little chat about gossip in the historical sense so that we can understand a bit better why gossip is such an innate part of the human experience, and maybe stop treating it as a social ill as opposed to a uniquely cool part of the human experience.

If gossip is human, it’s also true that people like to be haters about the fact that people talk about others. You may have heard that corny saying that goes, “Great minds discuss ideas; average minds discuss events; small minds discuss people.” Well guess what sweaty, you can discuss the idea of gossip and it turns out that at least in the global north people weren’t always so uptight about it.

At least in Europe people started to get way more thingy about what the Church called the “sins of the tongue” in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries.[1] We can track this in a couple of ways through literature. See in 1215 the Church had a get together – the Fourth Lateran Council – where they decided that all Christians needed to attended confession more regularly. As a part of this, they also made a series of guide books that gave confessors hints on exactly what could be confessed to them. Most of these include at least one chapter on ways gossip – or at least loose talk more generally – meant you were going to Hell.[2]

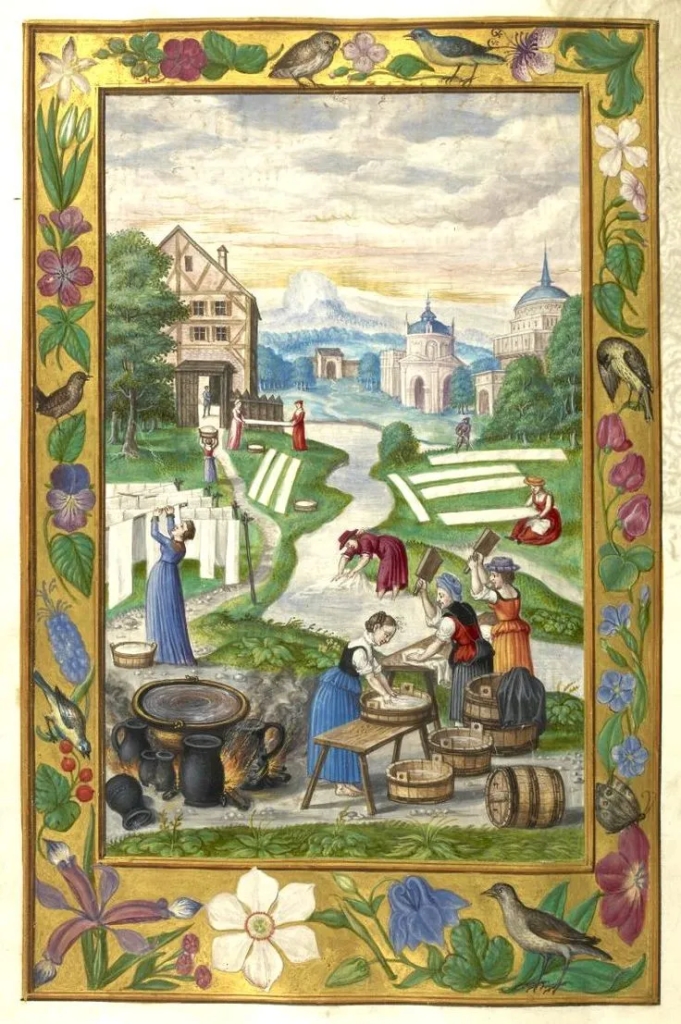

But it’s not just textual sources we find on the subject. We also see this same sort of concern crop up in art. Suddenly, you get a lot more hell mouths (shout out to one of my fav art tropes!) turn up not just in visual art but in places like mystery plays. Here, the hell mouth is meant to be understood not just as an entrance to Hell, but a way your soul might find its way down there, cuz you’re so busy talking trash.[3]

But the concern around gossiping about people is pretty closely tied not just to religious concerns, but to legal ones as well. Across medieval society someone’s reputation, or fama was considered an actual tangible asset that they quite literally owned – especially for men. [4] It was how someone knew that you were a trustworthy member of the community, or a good potential partner in business.[5] So if word got out that you were a scoundrel and a drunk, or what have you, it might mean that you would never hold public office or like, get invited to parties. As a result, increasingly in this period we see it hammered home that the only people who could pass judgement on the character of others were either the Church or the judicial system more generally. It couldn’t just be left up to word on the street.

If you are enjoying this post, why not support the blog by subscribing to the Patreon, from as little as £ 1 per month? It keeps the blog going, and you also get extra content. If not, that is chill too.

But here’s the thing: if we can see an up-tick in the condemnation of gossip it means that there was a point in time when it was also considered both chill and also cool because, actually it does the exact opposite of pushing people out – it brings people together.

The term gossip itself in English actually has a super cute origin – it just meant something that you engaged in with your “god-sibs”, aka your god-siblings or the peer group you grew up in and around.[6] SIn other words it was a term for exchanging information about and with members of your community – and a way of establishing who is your community.

The psychologist Robin Dunbar posits that the urge to chat shit with the homies is, in fact, what differentiates us from other primates, and allows us to have really big communities. A big way that primates create social groups is by engaging in social grooming – hanging out and picking the bugs off each other or whatever. This is super efficient. Anyone who is willing to do you a solid and deal with your bugs is obviously a friend. But like, how long have we got for bug picking all day, you know? So humans came up with talking to each other about each other as a handy stand in for picking off bugs.

As Dunbar puts it, language was developed as ‘an alternative mechanism for bonding in which the available social time was used more efficiently. Language appears to serve that function perfectly, precisely because it allows a significant increase in the size of the interaction group.’[7] How do you know someone is safe to hang out with? Well they know people you know and can exchange information about them. You can also give them information about problems in said peer group so they can be dealt with, much in the way that other primates remove unwanted bugs. Now you can have much larger peer groups because it doesn’t require physical maintenance.

And we absolutely do see language used in this way in the medieval period! One of the primary sources I am always harping on at you about – the Archdeacon Pavel of Janovice’s visitation protocol of 1379-1382 does exactly that.[8] My boy came in as archdeacon and went from parish to parish in Prague to ask the locals if there were any problems they had he could help them with. This is a brilliant way of embedding in your local community. You show up and ask how you can help and if there’s information you should know about the people there. It’s the equivalent of a baboon plopping down behind another and getting straight to the grooming. Like, babes, I am just here to help!

Anyway, the good people of Prague absolutely had a lot of problems with each other and proceeded to talk enough shit to span three years. Some of these complaints were totally understandable stuff to mention to the archdeacon; We get a lot of complaints, for example that their parish priest doesn’t speak the language of the community.[9] Other complained that their priests just … didn’t say mass at all??[10] That’s fine, and probably something that your religious authority should be alerted to immediately.

But a lot of others wanted to talk about the sex lives of the people in their community, which, damn girl same??? You are telling me your priest constructed a bunch of shacks in the churchyard that he rents out to people so they can bang in them??? [11] You mean to tell me, with a straight face, that your priest Wenceslas of Zap sees sex workers but thinks it’s OK because he sent them home immediately after he paid them?? [12] Talk. Your. Shit. To. Me!!!! YES!!!!!!!!!!!

And now I have told you about this. And you can be like “Oh man – that Wenceslas of Zap is NO GOOD.” It’s a beautiful tradition – running this man down. I love that I am doing this like seven hundred years after his death. That, to me, is hilarious and also good.

Now you could go ahead and say to me right now, “I mean sure Eleanor we all love the horny priest gossip, but if it’s being done in the context of a Church protocol does it count as gossip?” That is a very good question which I have stuffed in your mouth. You’re so insightful! The answer, I would argue, is both no and yes, from a legal and a social standpoint respectively.

So first up legally: no, it is not gossip. The Archdeacon asked if your priest was a hot little slut, and you told him he was. That is absolutely legit because this is a legal proceeding as far as the Church is concerned. But secondly, socially? Oh my god yes this is absolutely gossip?? You have the dirt on homeboy and proceeded to dish immediately. Maybe it’s legally defensible in this circumstance, but, uh, how did you get that info in the first place babes? You were out there in the street chatting the whole time always on Church business? Please be serious. You were gossiping. And from an anthropological standpoint, like, of course it’s gossip. The good people of Prague have a BUG which is this philandering ass priest Wenceslas in their midst and he needs to be picked TF off. We’re doing social grooming. That’s gossip.

But there’s a third element lurking here about why this is considered above board and definitely Not Gossip and it’s because gossip is usually connected not to men, but to women, and the femme presenting more generally. So, the Archdeaconate Protocol doesn’t count as gossip because it was undertaken by a man and he’s speaking exclusively to men – the only people who count in legal proceedings. If women were exchanging the exact same information it would be silly and hateful. Just some silly women condemning a fine upstanding member of the community! And a priest no less! Tut tut, for shame, have they no decency, etc.

This should give us some pause as modern people. It’s one thing in a medieval context to condemn gossip because people’s good reputations are important and blah blah blah. But that is still something that we hear now when people are exchanging information about exactly who is a wrongun, and particularly when women and femmes do it. Gossip is a powerful form of social grooming in that it allows us to curate our peer groups and remove unwanted or dangerous elements, like people who threaten us. The whisper network is a vital resource for spreading information when you might face blowback or ostracisation for blowing the whistle on someone behaving unacceptably.

I would argue, then, that the main reason we still tend to dismiss it is that gossip gets results and can be done by people who are socially disprivlidged. Oh, some dude’s reputation got damaged? Yeah, it probably needed to be! Set up a google alert for “youth pastor” and it will become very clear very quickly why people in positions of religious authority are super uncomfortable about you exchanging information about their sex lives. The same thing applies to people in positions of power more broadly. This is a powerful tool for community, and one that is wielded by people who are traditionally kept disempowered.

So with all that in mind I encourage you to continue to gossip, and to be aware of the incredible power you have to build community and keep your loved ones safe when you do.

TL/DR – if you don’t have anything nice to say? – come sit next to me.

[1] Wedward D. Craun, Lies, Slander, and Obscenity in Medieval English Literature: Pastoral Rhetoric, and the Deviant Speaker (Cambridge, 1997).

[2] Sandy Bardsley, ‘Sin, Speech, and Scolding in Late Medieval England’, in, Thelma S. Fenster and Daniel Lord Smail (eds.), Fama: The Politics of Talk and Reputation in Medieval Europe (Ithaca, N.Y. and London, 2003), p. 146.

[3] Patricia Dignan, Hellmouth and Villains: The Role of the Uncontrolled Mouth in Four Middle English Mystery Plays, PhD., University of Cincinnati, 1994.

[4] F.R. P. A. Kehurst, ‘Good Name, Reputation, and Notoriety in French Customary Law’, in, Thelma S. Fenster and Daniel Lord Smail (eds.), Fama: The Politics of Talk and Reputation in Medieval Europe (Ithaca, N.Y. and London, 2003), p. 79.

[5] Ibid., p. 75.

[6] R. I. M. Dunbar, ‘Gossip in Evolutionary Perspective’, Review of General Psychology 8.2 (2004): 100.

[7] Ibid., p. 102.

[8] Ivan Hlaváček and Zdeňka Hledíková (eds.), Protocollum visitationis archidiaconatus Pragensisannis 1379–1382 per Paulum de Janowicz archidiaconum Pragensem factae, (Prague, 1973).

[9] Ibid., p. 78.

[10] Ibid., p. 50; 68.

[11] ‘He then said, that they set wood in the cemetery around the church, under which bitter carnal commingling is often committed and he heard that permission had been given from the deacon, and, he had heard, the parish.’ Ibid., p. 53. (translations my own)

[12] ‘Wenceslaus of Zap, a priest, said that he occasionally comingled at night with a public woman and first thing in the morning after paying, he dismissed her.’ Ibid., pp. 254–255.

For more on medieval communication, see:

On secret romantic communications

On non-written communication in Norwich

For more on sexuality and the clergy, see:

On ‘the way of carnal lust’, Joan of Leeds, and the difficulty of clerical celibacy

Support the blog by subscribing to the Patreon, from as little as £ 1 per month! It’s the cool thing to do!

My book, The Once And Future Sex: Going Medieval on Women’s Roles in Society, is out now.

© Eleanor Janega, 2024

Kelsey from Normal Gossip has already mentioned the idea that gossip is a way that under privileged people (eg women) use to protect themselves. From memory, it was in the context of #MeToo and that google document that some women were circulating about dangerous men.

However, (speaking as a fairly WASPy 60+ male), I would suggest that most organisations have an informal version of the same. And because it’s maintained / supported by women, it’s ‘meaningless gossip’ (/S if you need it).

LikeLike