In London everyone is complaining because we are having one of those summers that just isn’t a summer. This happens, from time to time. Instead of temperatures in the twenties/seventies we get a progression of teens/sixties and a bunch of rain. The grass loves it, and most people complain about it, because somehow they have been fooled into believing that the Island of Britain is reliably a warm place. (Citation extremely needed.)

Now ya girl isn’t exactly overjoyed about summers like this, but fundamentally if it is between this and one of those climate change summers like we had last year where it was unrelentingly baking, I will take this every time. Also being from the South Puget Sound, I am aware that summers really do be like this sometimes. In my opinion it doesn’t really rain very much in London, and actually these non-summers are less frequent then I have been led to expect, so whatever.

Moreover, and more to the point – you think this is bad weather? Honey let me tell you about the summers of 1314-1316.

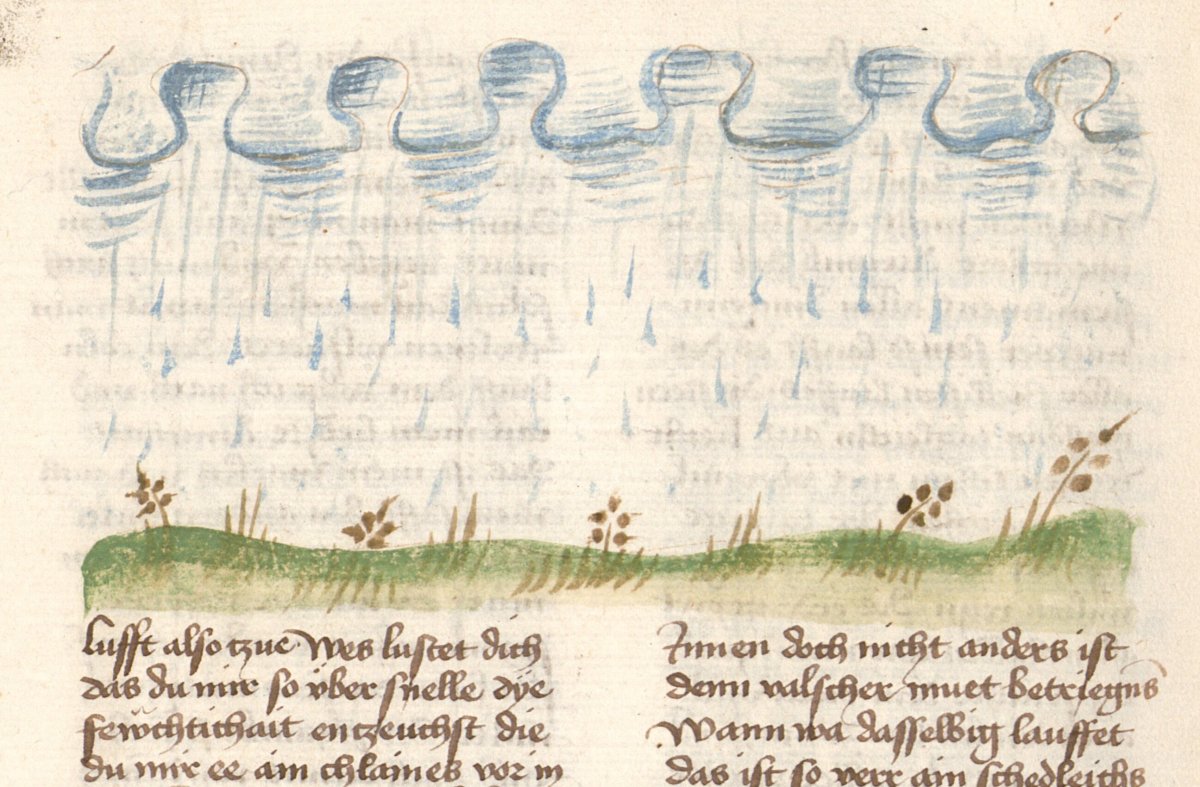

In 1314 things started to go really seriously wrong on the island of Britain in that it started raining in the winter did not stop. I am talking the type of rain that caused flooding so severe that livestock drowned. This is the type of rain that rotted crops out in the fields. Any livestock who had not drowned subsequently began to starve because they had nothing to eat. This, of course, also had knock-on effects for humans who are also dependent on stuff growing and also eating said livestock. Sure, some people had a bit of a surplus stored up to ride them through this time. However, the prices of everyday foodstuffs increased as their availability was extremely limited.

In 1314 it absolutely was possible to bring in food and crops from overseas, but it took a lot longer, and was fundamentally quite expensive. So, if you were a rich guy who worked in a guild in London, you might be able to suck up the prices and pay over the odds for some wheat that had come in from the lowlands. Things were real different, however, if you were a peasant living out in rural Gloucestershire, for example. A) you probably weren’t going to have that kind of cash to hand, and B) you probably weren’t even going to be offered the opportunity to buy it anyway. People send goods where they think they are going to get a return for that investment, and that is in places where there is a high concentration of people with a bunch of money to pay for it, i.e. in cities. TL/DR people in the countryside started starving.

This is of course, horrible, but one bad year doesn’t necessarily herald a problem that cannot be overcome. To combat the issues with price gouging. King Edward II (1284-1327) attempted to step in during the Spring of 1315 by setting limitations on the prices of food. The thing about people, though, is that a lot of them are dicks, especially when they are rich and think they are going to miss out on making money. As a result, a lot of food traders simply refused to sell their stock, and hoarded it instead. Edward was like, this is expressly the opposite of what I requested. And he attempted to encourage internal trade and also bring more wheat into the country.

Problem was with all of the dead livestock and what have you, England suddenly had a lot less of the one trading commodity that they usually used to get stuff from the continent – wool. So, persuading foreigners to give England stuff was hard. Also difficult for old Eddie was the fact that he was like, “LOL also I am King, so I am afraid I am about to requisition that food that you do have, because I am not going to starve, that is for plebs. K thanks bye.”[1] The point is, it didn’t exactly inspire people to start sharing.

All of this might have been a one off. Bad harvests happen. Kings aren’t usually popular. People bounce back, but the trouble is it kept raining, and the rain was not limited to the island of Britain.

The Summer of 1315 simply did not show up in Europe more generally. According to the Chronicle of Malmesbury, rain started falling on Pentecost (May 11) and fell so heavily that people thought that the prophecy of flooding hinted at in the book of Isaiah were being fulfilled.[2] That’s bad. Now the prices of crops everywhere in Northern Europe were elevated, and you couldn’t hope that a ship full of oats was going to come in from somewhere as yet untouched by bad weather. Vegetables, wheat, barley, and oates all saw huge mark-ups in their prices. There was also an increase in the price of salt, because the process of salt extraction is massively hampered in wet conditions. This is a problem, not just because salt is nice and makes food taste good. For medieval Europeans salt was the means of curing meat. So even if you managed to keep a pig alive and slaughter it, you suddenly didn’t have a way to preserve any of the meat for eating over time. (Go look up how large pigs are, and you will understand why it is a problem if you suddenly can’t make bacon from them.)

Now you know stuff was bad in 1315 because it started affecting rich dudes too. Edward “you have to give me food cuz I am the King” II got to St Albans when he was on procession on 10 August 1315 and apparently there was no bread anywhere in the city for anyone. Doesn’t matter if you are the king. No bread means no bread.

In 1316 it kept raining. Now stuff was dire. Up in the North of England in Northumbria where the weather was bad and locals were experiencing intermittent raids from the Scottish people began to eat their horses and dogs. Eating horses was particularly emblematic of the problem. If you ate your horse, it meant you had no hope of plowing in your crops later. So either the Northumbrians knew that there simply wasn’t going to be a decent enough year to plant, or they were so hungry that they couldn’t plan ahead anyway. Similarly, across the kingdom peasants began to eat the seed grain that is usually kept to the side for planting the next year.

It is around now that stuff started getting really creepy. According to the chronicler John of Trokelowe (? late thirteenth to mid-fourteenth century), among others, people began to eat each other.[3] Now this is, strictly speaking, a rumor. According to Johannes “many asserted” that “in many places” people were eating “children and strangers”. This may simply be hyperbole. However, the inclusion of these sort of rumors is indicative of their believability. Maybe people were not resorting to cannibalism, but things were bad enough that the writer and his audience thought it could be happening.

Also apparently common during this period was the abandonment of children. Rather than watch their kids starve, it was alleged that people just turned them out of their houses. This way you could tell yourself maybe they managed to fend for themselves. It is thought that this proclivity is what gave rise to the story of Hansel and Gretel, which we have written records of from at least 1500.

There were other similarly bad events, such as outbreaks of St Anthony’s fire, or ergotism, a sickness caused by eating fungus contaminated rye. This, according to our sources, sucks very much, and the “fire” part of the name refers to a burning sensation that those affected feel in their extremities caused by gangrene because blood flow is restricted. Other symptoms include nausea, insomnia, convulsions, skin sores, and hallucinations. Just the sort of stuff you want to be dealing with while starving.

All in all, apparently dead bodies were piling up in the streets of London, while in Paris the poor and labourers dropped dead on their feet.[4] Friends, it was bad.

Luckily by 1317 the sun came out. This did not make everything alright automatically because of, you know, the whole lack of seed grain and any animals to help plow your fields thing. But it was better. Admittedly this is not hard, but still. All in all it would take until 1321 for food supplies to get back to their pre-1314 levels and the period of 1314-1317. We estimate the death toll from all this bad weather at about ten to twenty-five percent of the population in some towns. This time period is now referred to as The Great Famine and it marks a decisive split from a period of rapid expansion of the European population that had been happening since the eleventh century.

Because the Black Death would pop up about twenty years after the Great Famine, we tend to overlook what would usually be a huge topic of study. After all, this was a genuinely awful time, which led to a generalised societal breakdown, and caused many to believe that the Apocalypse might be at hand. It is just that in comparison to a mortality rate of about sixty percent as we see as a result of the Black Death, suddenly twenty-fiver percent death starts looking like small potatoes.

Now, I don’t want to get all fallacy of relative privation on you all. A crap summer is a crap summer, and after our own little pandemic it does indeed feel like a kick in the teeth to have out access to outside curtailed by rain, especially at a time when outside feels like it is maybe the only safe place to be. What I am saying, however, is that we can lick our wounds without acting like this is the worst summer to ever happen in England. This stuff happens. Just pack an umbrella – you’ll be right.

[1] William Chester Jordan, The Great Famine: Northern Europe in the early fourteenth century. (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1996), pp. 171-174.

[2] Vita Edwardi Secundi, (Chronicles of the Reigns of Edward I and Edward II), Vol. II, Rolls Series, (London, 1883), p. 214

[3] “Carnes quidem cummunes, et ad vescendum licitae, strictae erant nimis; sed carnes equinae pretiosae eis fuerant, qui canes pingues furabantur, et ut multi asserebant, tam viri quam mulieres parvulos suos, et etiam alienos, in multis locis comedebant.” Johannes de Trokelowe, Annales, (Chronica Monasterii S. Albani), Rolls Series, (London, 1866) p. 95.

[4] Ibid. p. 94; Grandes Chroniques de France, Vol. V (Paris: Paulin, 1838), p. 227

For more on bad stuff that happened in the fourteenth century, see:

On collapsing time, or, not everyone will be taken into the future

Plague Police roundup, or, I am tired, and you people give me no peace

Chatting about plague for HistFest

A Black Death reading list

On individual blame for global crisis

Not every pandemic is the Black Death

On the plague, sex, and rebellion