I used to teach an introductory course on medieval history at a university here in London where we had a week dedicated to introducing the concept of courtly love. If the students so chose, they could later write an essay on the topic. The question that they were asked to answer was: “What does courtly love literature tell us about women in medieval society?” It was a trick question. I have been thinking about the reasons why that was a trick question lately, because over the past few weeks I have been learning a lot about Jacques Lacan.

Read more: On men, romance, and trick questionsThis process of learning was largely unwilling. See there’s a very good new book out called Event Horizon: Sexuality, Politics, Online Culture, and the Limits of Capitalism by Bonni Rambatan and Jacob Johanssen. It does pretty much what it says on the tin and has a lot of Lacanian theory in it. Said book was the subject of a two-part podcast over at Culture, Sex, Relationships, which means my partner had to learn a lot about Lacan in order to host said podcast. That means that I spent a bunch of time hearing about Lacan and then had to start learning about his work to keep up. And that is what is called an “affective flow”, which is actually a Deleuzian concept, but Deleuze and Guttari were largely critiquing Lacan. SO now you know.

Anyway, because I am who I am, the stuff that I was most interested in was, of course, the sex stuff, and I got really interested in Lacanian ideas like the sexual non-relation and such and such. As a result, I started to think about how Lacan’s ideas tracked on to medieval ideas about sex and relationships. Lo and behold old Jacques over here had actually written about that, and so today I thought we would talk about psychoanalysis and what it has to do with medieval people, and our own romance culture and why this essay was a trap, much like many of our concepts of romance.

The deal with Lacan is that a lot of his work, especially about sex is actually Freudian. See Freud has this concept of that he calls das Ding (or the thing, if you don’t speak the incredibly complex German here) which hinges on the idea that we live in a world where our deepest (and probably most narcissistic) desires go unanswered in general. Moreover, when we question the world we don’t really get any answers. In this conception das Ding, or as Lacan calls it object petit a (He likes to do things like algebraic equations, ok? Look I don’t want to get into it.) is therefore a sort of object that sets that unanswerable desire in motion. But here is das Ding (see what I did there?) – even though we are driven by our desires into action we never really get the thing we want. We just sorta like … circle around it, wanting it.[1]

Now, if you all have been paying attention to everything that I have written about courtly love before, this will immediately make you say, “Ah, hmmmm. I see. Ah.” To those people – sorry we have to do a quick run down again. To newcomers, what you need to understand about courtly love it that it is a type of romantic literature written by single dudes about the married ladies that they have a boner for at court.

Now this means that the men and women in question have to overcome rather a lot of social issues in order to be in love or whatever – namely the fact that they weren’t supposed to be communicating. Cuz the women were married to other people. I just cannot stress that enough how married to other people they were.

Because of this, the very conception of love in these cases is pretty much exactly the same thing as das Ding. To whit, a priest who has no business writing about this subject, and author of De Amore or The Art of Courtly Love, the pick up artist guidebook for aspiring horny knights, describes love as ‘a certain inborn suffering derived from the sight of and excessive meditation upon the beauty of the opposite sex, which causes each one to wish above all things the embraces of the other and by common desire to carry out all of love’s precepts in the other’s embrace.’[2] So right out of the gate there we have ‘love is pain because of your desire for a thing which you are probably not going to get because all of society has set itself up to prevent you from getting it.’ So far, so das Ding.

If you are enjoying this post, why not support the blog by subscribing to the Patreon, from as little as £ 1 per month? It keeps the blog going, and you also get extra content. If not, that is chill too.

Moreover, we have the idea that this suffering and unfulfilled desire is just a part of the human condition, or as Capellanus puts it, it ‘is inborn … because if you will look at the truth and distinguish carefully you will see that it does not arise out of action; only from the reflection of the mind upon what it sees does this suffering come. For when a man sees some woman fit for love and shaped according to his taste, he begins at once to lust after her in his heart; then the more he thinks about her the more he burns with love, until he comes to a fuller meditation. … Then after he has come to this complete meditation, love cannot hold the reins, but he proceeds at once to action; straightaway he strives to get a helper and to find an intermediary. He begins to seek a place and a time opportune for talking. … This inborn suffering comes, therefore from seeing and meditating.’[3]

In other words, ‘love’ within the courtly construct has absolutely nothing to do with falling in love with a real live person, who has a rich interior life, flaws, and wants, needs, and desires of her own. Nope. It is about seeing a hottie and then just making her into whatever it is you desire in your head and then attempting to act on that desire as a result. She is an idealised object created in the heads of men that sparks action.

Because the woman in question is just an object, the men involved are able to predict her behaviour and indeed her reaction to being wooed. Hence the whole, ‘De Amore is a pick up artist manual’ thing, as I have written about before. Capellanus feels confident that he can tell men how the women who are ‘fit to love’ will react to being hit on. Andreas doesn’t see what Lacan does that ‘a cold, distanced, inhuman partner’ whose actions can be predicted like some sort of automaton, is probably not going to be very sexy, because he is not a psychoanalyst.[4] Instead, Capellanus thinks that this means that the activity that men’s desire sparks will have a positive outcome – which is that the woman in question will probably fall in love with you after you chat her up for roughly ten minutes.

But what does being in love actually mean in the courtly love sense? Turns out it was mostly just, like, vibing. After all, your girlfriend is married, and men and women are largely kept segregated from each other even in public spaces at court. Even if you were to find some alone time with the woman in question you really had to watch out for getting her pregnant because pretty much her whole job was to get knocked up by her husband, not you, some horny young dude. Of course people got around this by really going to town on some sodomy, but for the most part the whole courtly love thing didn’t really involve what you and I might call an ‘actual relationship’, or, ‘speaking to each other’, or, ‘any kind of basic communication at all whatsoever’.

But don’t worry – that was supposed to be a good thing. According to Capellanus, the fact that you might never actually speak to the object of your affection was a good thing because, when ‘lovers see each other rarely and with difficulty … the more do they desire for them and their feeling of love increase.’[5] And I mean, yeah I bet, because if you never actually see or speak to the object of your desire then they remain that – an object – for you to project your own wants and ideas on without being troubled by the human aspects of the other person. To put it another way, the women in these relationships aren’t so much women, and the love isn’t so much love, so much as they and the love in question are mirrors that reflect back the desires of man.[6] The men here aren’t in love with a woman, they are in love with their own desire, and to an extent, themselves.

And that right there is the crux of the trick in the essay question. The thing about reading courtly love literature is that it doesn’t actually tell us anything about women in medieval society – it tells us about men in medieval society. It is literature written by men, for men, about imaginary women who just so happen to act in exactly the way the want them to. The only thing that it tells us about women in medieval society is that being one kinda sucked because no one actually cared about who you were or what you thought.

Now I am aware that I have just made you read 1500 words on psychoanalytical philosophy and also a genre of literature from the Middle Ages, and I would not be offended if you were wondering why the hell I have done so. But there is a reason – and it is that these ideas about love actually do proliferate in our own romance culture today. We encourage people to think that there is some sort of magical ‘one’ out there in the universe who will complete them. We reify obsession with and excessive meditation on our romantic partners as proof of the validity of love. And we still have a thriving industry that tells men that women can be predicted and gamed into behaving in the way that men want.

Considering where these ideas about romance come from, and approaching them from a psychoanalytical angle, means that we can critique and ultimately discard them. We are never going to be made whole by romance or another person and we shouldn’t try to be. If you spend all your time waiting for ‘the one’ to come along and fix your life then you are going to be in for a terrible shock, and an unending string of relationships, when you eventually get into a relationship with a person and find that they do not in fact make you ‘complete’. The only way that a love predicated on this idea can prosper is specifically in the courtly love sense where you never see the other person and can keep this ridiculous conception going until the end of time.

Probably that is not something to strive for! I am just saying!

Instead, a nice thing to do is get comfortable with the fact that you will likely always have a drive for something more, and realise that it is probably unrealistic to follow that drive, which is ultimately the goal of analysis here. We can choose to have real relationships with other humans who are complex, messy, and flawed. We don’t have to look for our absolution or our completion in romance. There is a whole world of real people out there that we can connect with in imperfect and ultimately much more satisfying ways. That is where to put your attention.

Anyway, IDK I am probably more of a Deleuzian. I just kinda got distracted.

[1] Jaques Lacan, The Seminar. Book XI. The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis, 1964, trans Alan Sheridan, (London: Hogarth Press and Institute of Psycho-Analysis, 1977), p. 179

[2] Andreas Capellanus, The Art of Courtly Love, trans. John Jay Perry, (New York: Columbia University Press, 1990), p. 28

[3] Ibid., p. 29.

[4] Slavoj Žižek, The Metastases of Enjoyment: Six Essays on Woman and Causality (Wo Es War). (London; New York: Verso, 1994), p. 90.

[5] Capellanus, The Art of Courtly Love, p.153.

[6] Žižek, The Metastases of Enjoyment, p. 91.

For more on courtly love, see:

On courtly love and pickup artists

On incels and courtly love

On Hotline Bling and courtly love

On courtly love, sexual coercion, and killing your idols

On pickup lines

Support the blog by subscribing to the Patreon, from as little as £ 1 per month! It’s the cool thing to do!

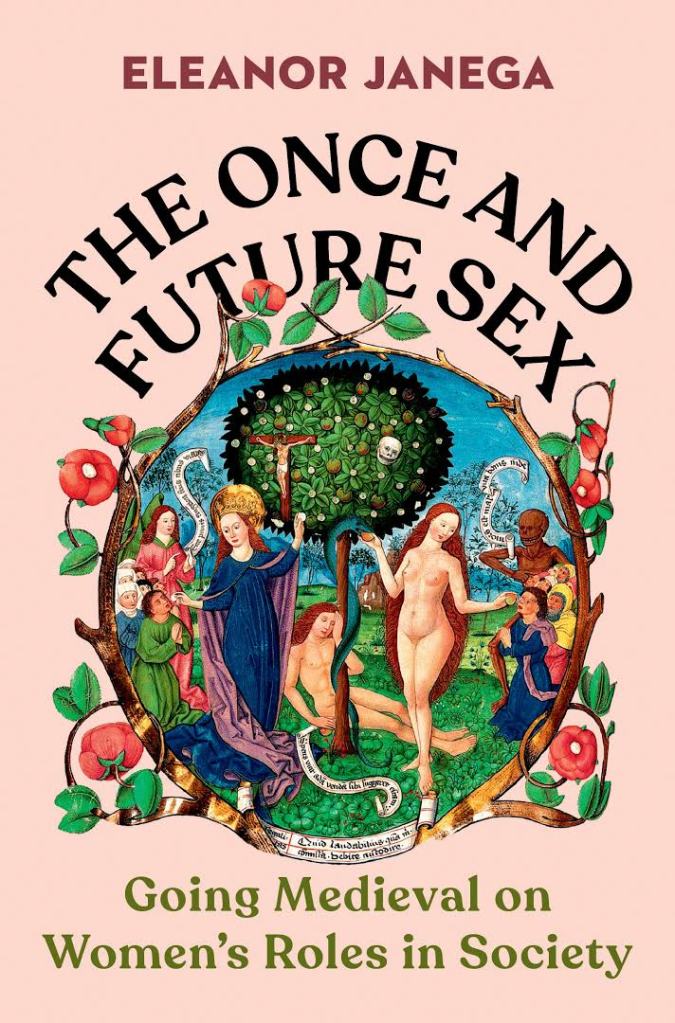

My book, The Once And Future Sex: Going Medieval on Women’s Roles in Society, is out now.

© Eleanor Janega, 2024

A woman I knew long ago was an admirer of C.S. Lewis’ “the Allegiry of Love,” though I never read it and couldn’t tell you what she liked about it. Do you know it, and if so what do you think of it? I have a pretty low opinion of Lewis in general.

LikeLike

I haven’t read it, but now I am going to have to just to be shady.

LikeLike

To a large degree “courtly love” has been replaced by “hook-ups” or “friends with benefits”.

LikeLike

I mean I think over all courtly love is a form of friends with benefits…

LikeLike

OK, so why am I thinking of INCELS right now. A dark side of this coin? Love reading your stuff btw.

LikeLike

OMG yes you are spot on here.

LikeLiked by 1 person