Last week, I was having a nice little chat on BlueSky, my go-to site for chatting shit and avoiding work now that twitter is unusable, with some very nice people, and I was asked a thoughtful question about how we talk about the different eras of the Middle Ages.

This made me realise that there are all sorts of weird technical aspects of history that you, my beloved readers, probably don’t know off the top of your heads and it would behoove me to take the time to explain them to you now and then. I mean, just so that I am not always yelling at you about more complex topics before you have a background.

Thus – behold – a new semi-regular series wherein we will get to grips with technicalities about medieval history: Let me explain something to you. The first installation of which is indeed about what we call different parts of the Middle Ages and why, aka periodisation.

So like good little historians let’s define our terms before we set out. When I say periodisation, what I mean is the division of parts of history into distinct periods. I am pretty sure you can come with me on that one.

Why do we do that? Well it’s us being slightly lazy, is why. Periodisation is what allows us to make generalisations about various time frames and also it just makes the conversation easier. As I have said before, it’s something historians do to the past, not something that the people who live there do themselves. No one wakes up one day and says, “Oh I just checked the calendar, it’s the early modern period now.” That is something that historians engage in retroactively.

As I have written about before, that’s how you get the very concept of a Middle Ages in the first place. It is a pretty European-centric way of delineating things, because it starts with the “fall” of the Roman Empire in 476, and the ends …. IDK like maybe in the sixteenth century?[1] Maybe in the late fifteenth? Basically if you can see Protestants you’ve gone too far.

Now this can get really difficult to apply to other places. Say, for example, China, which has a lot more recorded history to grapple with, and a lively debate about how to periodise that.[2] However, increasingly we are using the term to apply to the world as a whole. As a part of that we also have the term “Global Middle Ages” and a new and exciting area of studying pertaining to it, because it’s sort of impossible to pretend that Europe existed in a vacuum and wasn’t connected to the rest of the world. As Holmes and Standen have put it, the Middle Ages “were a period of dynamic change and experiment when no single part of the world achieved hegemonic status.”[3] So even if we got to our term through a very specifically European route, it is sort of helpful to apply it world-wide to see how these interconnected places were relating.

So that’s the Middle Ages more broadly, but if you have been paying attention, you’ll note that 476 to 1500 or so is a very very long time, and – would you believe it – things actually change over that arc. So, we further break the period down into three sub-sections. And there are, of course bits that presage it, and those that come after it which are also in relation to it, and which is is helpful to understand.

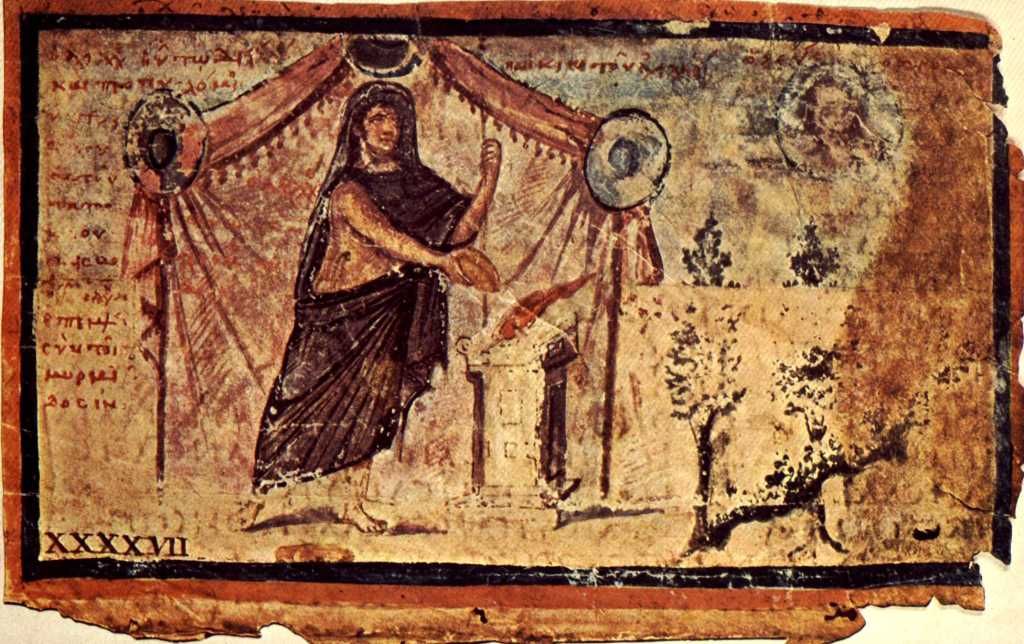

The period right before the Middle Ages starts is usually referred to as the “Late Antique Period”. If you are in Europe this is when you get stuff like the rise of Constantinople, the split of the Roman Empire into the East and West, and also the age of the Church Fathers who spend a lot of time trying to establish what Christianity is going to be. Medieval historians of religion or society, like myself, often have to do a lot of reading from this period because medieval philosophers are very much in a continuum of knowledge with guys like St Augustine of Hippo (354-430) and St Jerome (c. 342-420), for example.

Anyway some thirty six years after St Augustine dies Odoacer (c. 433-493) kicks the child Emperor Romulus Augustus (C. 465-511) off the Western Roman throne in Ravenna and ta-dah – you have found yourself in the Early Medieval period. Not that anyone thought that at the time. Now, we used to call in the Dark Ages, (because of a reference to the lack of sources, and not intellectual decline). However, it turns out non-historians couldn’t be trusted with the term and used it totally incorrectly to mean “the bad time when people were stupid, not like me a person who has never learned or read about this period but nonetheless runs their mouth about it.” So now we say Early Middle Ages because we are very tired and cannot know peace.

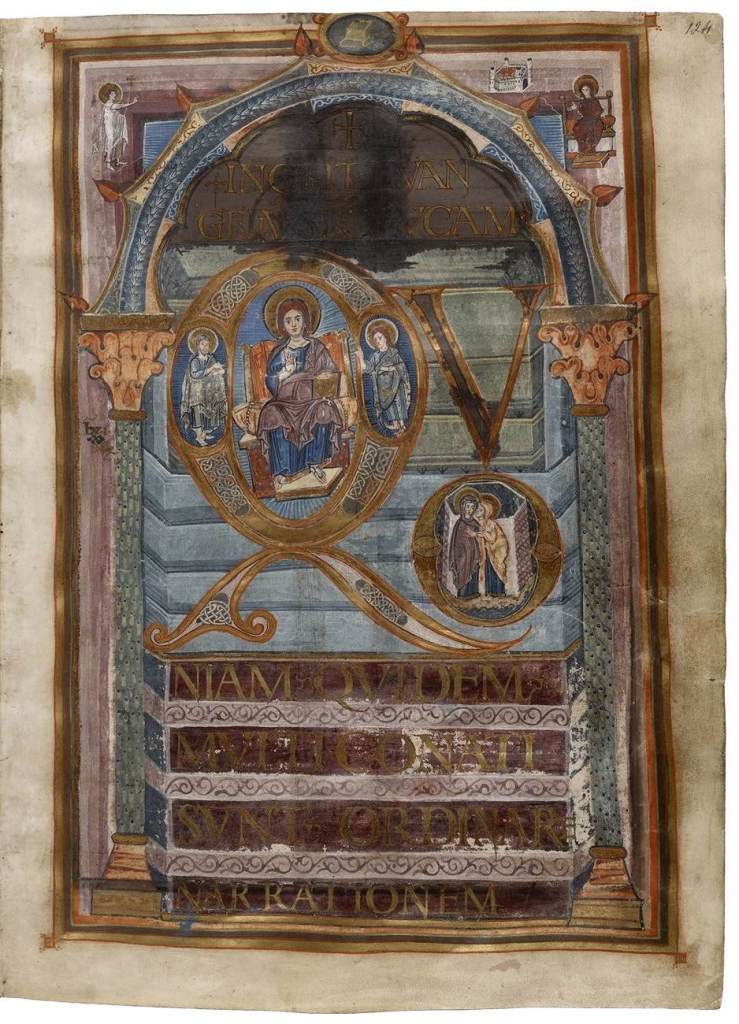

Bibliothèque Nationale MS Lat. 8850, fol. 124r.

The Early Middle Ages, ironically, has a bunch of stuff in it that people like, even as they are talking shit. For example, this is where you will find your boy Charlemagne (748-814) and he starts his very own renaissance. It’s when the majority of the Viking Age takes place. Constantinople is absolutely popping off at this point. It’s when Islam comes into being, and the Islamic Golden Age begins! It’s very very fucking cool, is my point, and in no way a time when everyone was rolling in the mud.

If you are enjoying this post, why not support the blog by subscribing to the Patreon, from as little as £ 1 per month? It keeps the blog going, and you also get extra content. If not, that is chill too.

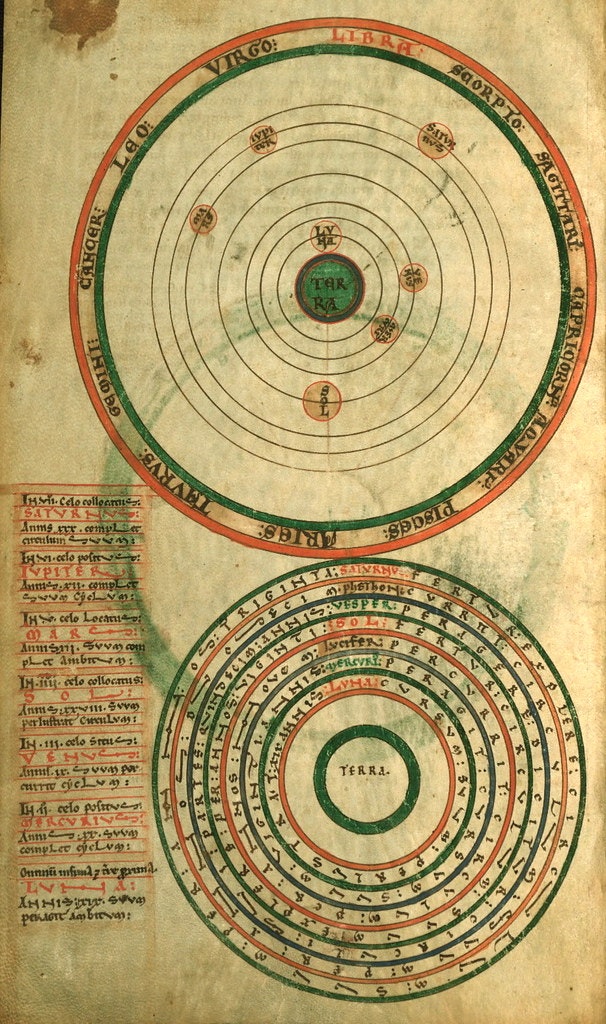

As the medieval period progresses we then hit the High Middle Ages in 1000 CE. Now, look. I understand I have been very wishy-washy about when the medieval period ends, and that 476 isn’t a satisfyingly round date for when it begins either, but IDK what to tell you. We’re just saying that the year 1000 is a fresh era because it’s cool and fun to do so. We say “High Middle Ages” as opposed to “Mid” or “Middle Middle Ages” because that is confusing and sounds stupid. So high it is.

The High Middle Ages is once again extremely cool and it’s really when you start to see a lot of the things that we associate with the Middle Ages come into being. Courtly Love? Oh yeah that’s high medieval. It’s when you have a huge period of urbanisation in Europe, which I love. You get the twelfth century Renaissance and the invention of the university. There’s also uncool stuff that happened like, for example, the Crusades, but frankly you cannot win them all. It’s also when the Church starts to become a real legal mechanism and to operate as such. I think you can kinda take that either as a good or a bad thing depending on what they are weighing in on. There’s also the Mongol conquests which are also kinda ambivalent, but I would argue anything leading to the Pax Mongolica is good, and of course that if Temujin was white we’d talk about them differently.

Much in the way that the High Middle Ages gets a nice round number to begin with so does the Late Middle Ages, and here we just say 1300. However, an argument can be made that it actually kicks off in 1315 when you hit the Great Famine, which I have of course talked about before.

I bring this up because it’s not just the years that make the Late Middle Ages distinct from the High Middle Ages, but the general vibe. Which gets a lot worse. You have a massive drop in population because of not only the Great Famine, but also the Black Death. You have a lot of peasants’ revolts because everything sucks and is bad. Again, I might argue this is ambivalent because actually it’s very cool to revolt against your oppressors, but the fact that it had to come to that is probably bad. As the period progresses you then also get good stuff like the Lollards and the Hussites inventing cool new ways to be Christian, and if you are the Hussites winning wars about it. This is also the period when a lot of the medieval literature we know and love gets written. You get Dante’s Divine Comedy. You get Boccaccio’s Decameron. You get The Canterbury Tales. You also just get better source survival more generally because it’s closer in time to us.

You then wrap up the medieval period by hitting the Early Modern Period. Again, it’s hard to say exactly when that starts, but defo it is happening by the sixteenth century. It’s when a lot of the bad stuff that medieval people get blamed for goes down. The Spanish Inquisition? Early Modern. The Witch Panics? Early Modern. There’s also all this terrible stuff like the start of the Atlantic Slave Trade, the Wars of Religion, and settler colonialism. But apparently that’s all fine, cuz a couple of Italian guys got to buy some very expensive art so stuff was better? Anyway, when all that stuff is happening you are being very modern indeed.

These categories are all, of course, inventions as I say. That means you don’t need to worry too too much about getting everything exactly write. I mean I am not gonna be mad if you, for example, call something from the eleventh century Early Medieval. I probably will be mad if you call something bad from the Early Modern Period medieval though, because if you do you are probably doing it to be a dick. I will also get mad if you call something from the Late Medieval Period that you like “Renaissance” because, again, you are doing it to be a dick. Honest mistakes? Those are fine. Trying to classify a thousand years of history as the only time when bad or ignorant stuff happened? That’s bad. Generally trying to be a bit more informed about history and getting your periodisation right? That’s excellent.

We can do it friends! We can be a bit more precise and communicate more effectively. I believe in us!

[1] On trying to periodise the Middle Ages generally, a good introduction is Torgeir Landro, “Periodization and Temporal Boundaries–Defining the Middle Ages.” Discussing Borders, Escaping Traps: Transdisciplinary and Transspatial Approaches (2019): 17.

[2] A nice basic introduction is Chun-shu Chang, “The Periodization of Chinese History: A Survey of Major Schemes and Hypotheses”. <Accessed 26 Feburary 2024>

[3] Catherine Holmes, Naomi Standen, Introduction: Towards a Global Middle Ages, Past & Present, Volume 238, Issue suppl_13, November 2018, p. 2, https://doi.org/10.1093/pastj/gty030.

For more on periodisation, see:

There’s no such thing as the Dark Ages, but OK

JFC calm down about the medieval Church

You are not, in fact, the granddaughter of the witches the couldn’t burn

On collapsing time, or, not everyone will be taken into the future

Support the blog by subscribing to the Patreon, from as little as £ 1 per month! It’s the cool thing to do!

My book, The Once And Future Sex: Going Medieval on Women’s Roles in Society, is out now.

© Eleanor Janega, 2025

We have to give those Early and High Medieval clergy a little credit on the witchcraft thing. When someone came to them claiming to have had sex with the devil, their response was, “You were dreaming, pal. Say a few Hail Marys to keep Satan out of your dreams. Have a nice day.”

As you say, it was the Early Moderns who decided to squash people under big rocks until they lied about who were their accomplices.

From what I’ve read, the reification of witchcraft was a useful tool for enforcing social norms, settling scores, and fighting the Reformation/Counter-Reformation. The loss of the One Church made it more relevant. Does that make sense to you?

LikeLike

It’s my understanding a small number of people who claimed to be witches were burned in the Middle Ages, but not for witchcraft—what you describe as the response to someone claiming to have a witchy experience was pretty much the Church’s position on witchcraft generally. But if you claimed to have commerce with Satan and/or pagan gods on the regular and _refuse to shut up about it_, then the Church’s position of “pagan gods aren’t real and Satan has no power over good Christians” means that your willful refusal to go along with them is not a mild indiscretion, but heresy, and they’ll burn you for that.

Like, Malleus Maleficarum was Late Medieval, alright (really late Medieval, so that you could argue it’s Early Modern), but it was very much a heterodox work, and continued to be considered as such well into the Early Modern period.

LikeLike

Yeah absolutely the case and the distinction here is you aren’t being burnt for witchcraft, you are being burnt for heresy. That’s exactly it.

LikeLike