I’ve been thinking a lot about ghosts lately. No, not because it’s October. That sort of seasonal interest in ghosts is for amateurs, and your girlie is thinking about ghosts 24/7 365. I don’t get ready for spooky season, I am spooky season. Regardless! I was once again enjoying the delights of the Byland Abbey ghost stories and thought it would be a cute seasonal treat for us to consider them all today, because I don’t expect you to be as committed to the creepy girl life as I am.

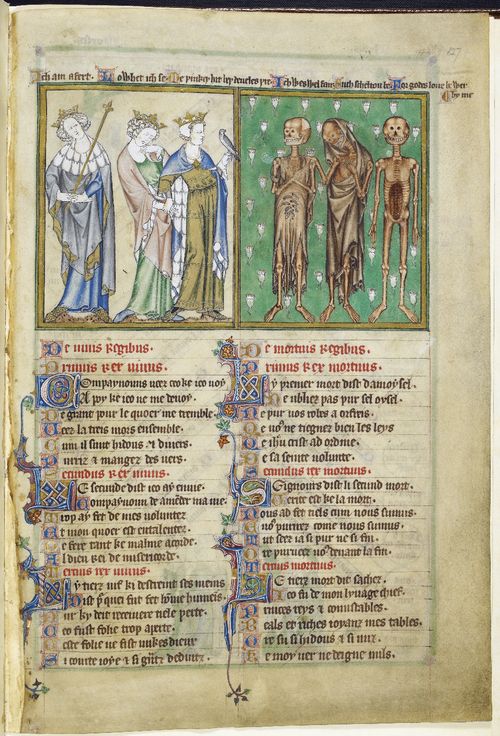

The Byland Abbey ghost stories are famous as medieval ghost stories go, having been identified by legendary spooky guy, medievalist, and all-around weirdo (positive? Maybe? IDK my boy didn’t like women, so I am not sure I have to like him, personally. I love his ghost stories though. Like, a lot.) M. R. James (1862-1936). They appeared in what is now British Library MS Royal 15, A. XX (some of which you can see here). It hails from Byland Abbey and was likely compiled at the end of the twelfth and beginning of the thirteenth centuries. It has exactly the sort of stuff that you would expect a bunch of medieval monks in Yorkshire to be writing down. Namely Cicero. (It’s always bloody Cicero.) But what James found was entirely cooler than that –at the end of the book where there were a few pages of blank parchment one enterprising monk a few centuries later (likely around 1400) had decided to write down a bunch of ghost stories from the local area.

These are incredibly cool because they give us a glimpse into what people (or at least monks) in the late medieval people think of as scary, and what I think is interesting is that it bears only a passing resemblance to what we think of as frightening today, and has a lot more to do with animals.

This might strike a lot of us now as strange because animals are not exactly in our top “stuff is scary” lists anymore these days. That doesn’t mean they don’t play a large factor in older ideas of the macabre, however. As Delyth Badder and Mark Norman remind us in The Folklore of Wales: Ghosts, ‘As Professor Owen Davies has noted, phantom animal sightings reported to the Society of Psychical Research across Britain in general make up ‘only a very small proportion of cases”‘.[1] The authors go on to note that in Wales, especially in folk belief, animals make up a much larger proportion of ghost sightings, which is interesting when contrasted with the tales from Byland Abbey.

For example, the very first ghost story involves a labourer who is trying to carry a peck (about 9 liters) of beans home on his horse. The horse meets with an accident and so the man has to continue on by himself. This is when he sees the ghost, ‘as it were a horse standing on its hind feet and holding up its fore feet. In alar he forbade the horse in the name of Jesus Christ to do him any harm. Upon this it went with him in the shape of a horse, and in a little while appeared to him in the likeness of a revolving hay-cock [a small pile of hay left to dry] with a light in the middle; to which the man said, “God forbid that you should being evil upon me.”‘[2]

So, yeah. Scary horse, scary hay pile. As you do.

Meanwhile, the second, and arguably most famous of the tales – that of Snowball the tailor – similarly starts out with said Snowball getting the heebie jeebies when on the road ‘he heard as it were the sound of ducks washing themselves in the beck, and soon after he saw as it were a raven that flew round his face and came down to the earth, and struck the ground with its winds as though it were on the point of death … and he saw sparks of fire shooting from the sides of the raven.’[3]

To be fair I guess this is slightly scarier than the horse and the haycock in that … yeah it’s weird to see a raven with fire shooting out of its sides, and I think I wouldn’t like that. Still if I was trying to conjure a scary story it probably wouldn’t involve the sounds of duckies having a little bath.

Later in the story, the ghost reappears, ‘in the likeness of a dog with a chain on its neck.’[4] Here the ghost has at least upped its game and turned into an animal that can cause us bodily harm. Finally, in the story’s denouement, the ghost appears a final time as a ‘she-goat’ that ‘fell prone upon the ground, and rose up again in the likeness of a man of great stature, horrible and thin, and like one of the dead kings in pictures.’[5]

K so here we find the ghost eventually morph from an animal into a (scary) man, which again I can agree is creepy. But a goat in and of itself? Doesn’t really do it for me.

Poor Snowball finally sees one more ghostly animal ‘a bullock without a mouth or eyes or ears’ who is the ghost of a man who killed a pregnant woman.[6] He is unable to speak to Snowball when conjured (he doesn’t have a mouth, after all) indicating that he is beyond absolution, unlike the main ghost Snowball sees as a raven, dog, and she goat.

Again here, I am not particularly scared. I think I would be more scared of the lack of eyes, ears, and mouth on this poor little bull than I would be of the bull itself. One imagines that perhaps it is linked to a concept of masculine excess (bulls are quite macho, after all) and therefore signifies that the man became violent like a bull might do. But that is just a guess on my part.

Overall, the animal that crops up the most in these stories is definitely horses. We see scary horses appear in tale VII when William of Bradeforth was returning to New Place from Ampleforth, ‘and as he was returning by the road he heard a terrible voice shouting far behind him, and as it were on the hill side; and a little after it cried again in like manner but nearer, and the third time it screamed at the crossroads ahead of him; and at last he saw a pale horse and his dog barked a little but then hid itself in great fear between the legs of said William.’[7]

Horses may be linked to worries about the apocalypse. We all know about the four horsemen of the apocalypse, and we know that a pale horse there is a symbol of death – right? Of course we do. We are all into apocalyptic thought here. But just a reminder in case you haven’t thought about it in a while, in Revelation 6:7-8 John of Patmos reports:

‘And when he [the Lamb of God] had opened the fourth seal, I heard the voice of the fourth beast say, Come and see.

And I looked, and behold a pale horse: and his name that sat on him was Death, and Hell followed with him. And power was given unto them over the fourth part of the earth, to kill with sword, and with hunger, and with death, and with the beasts of the earth.’

So, horses are an understandable symbol of death from a medieval standpoint. However, horses aren’t instantly legible as freaky to us in the same way that William and the unnamed labourer in the first story find them to be. This isn’t to say, as already mentioned, that we don’t still have horse ghost stories, and they are particularly popular in Ireland and Wales. They just don’t have the same zing to a modern audience as they do to the compiler of the Byland story.[8]

So, in all the scary animal ghosts of Byland are: horses, ducks, ravens, a young bull, and a she goat.

This is interesting because it’s probably not the list of scary animals you would expect. The raven? Maybe! After all, Edgar Allen Poe! The goat perhaps a bit more so. It’s very Black Phillip. Very living deliciously, etc.

If you are enjoying this post, why not support the blog by subscribing to the Patreon, from as little as £ 1 per month? It keeps the blog going, and you also get extra content. If not, that is chill too.

However, this association with goats very specifically as evil is a little bit more modern than it is medieval. This association is likely initially linked to Matthew 25:31-46, one of Jesus’s parables. ‘When the Son of Man comes in his glory, and all the angels with him, he will sit on his glorious throne. All the nations will be gathered before him, and he will separate the people one from another as a shepherd separates the sheep from the goats. He will put the sheep on his right and the goats on his left.’

Goats here are a stand in for those who didn’t help the poor and sick, and they end up in hell, etc.

Goats do at times pop up in the later medieval period, especially among weirdo inquisitors. Nicolas Jacquier (d. 1472) for example, accused one Guillaume Edeline of heresy in 1453. After some light questioning (i.e. torture) he claimed to have denied God, worshiped the devil in the form of a goat, and engaged in some light orgy stuff at a Sabbat.[9] This is pretty standard stuff that inquisitors put in the mouths of their victims. It’s always an inverted mass and a random animal or something.

So naughty goats exist in those with a biblically-minded imagination. That much is clear. However, it isn’t what I would call incredibly prevalent necessarily. They don’t even pop up in the Malleus Maleficarum where we see a lot of our more common witchcraft/demon tropes introduced and solidified.

However it’s at this point in the very late medieval period/early modern period that they begin to appear more often – just like the early modern period is the hay-day for witchcraft accusations. We see them really arrive in particular with engravings like those of Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528) who made the decision to depict a witch as an old woman riding backwards naked on a goat and – hey presto! – goats were the creepy thing to include in stories.

They take enough of a hold of the early modern imagination that in the modern era we began to retrofit goats to be included into stories from the past.

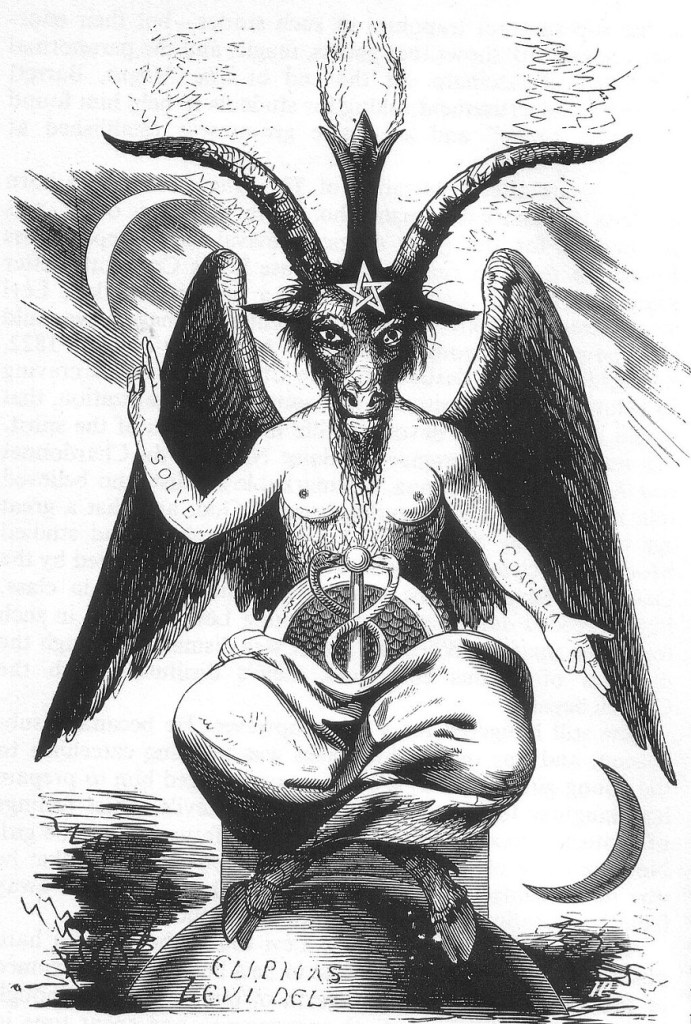

For example, during the suppression of the Knights Templar they were accused of worshipping something called Baphomet. We … don’t exactly know what that was. Maybe it was an idol? Maybe a series of wooden heads? Maybe a painting?[10] All we know is an idol comes up a lot in all of the confessions forced through torture that follow the standard heretical sex-panic model. Brother Philippe Agate, who had been the commander of Sainte-Vaubourt, for example, claimed that ‘he was made to deny Christ there times, and to spit on the cross, engage in indecent kisses, and agree to lie carnally with brothers of the order is asked; he saw an idol on a table, and he believed that his belt had been touched to the idol.’[11] Again, pretty standard stuff from some poor guy who just wanted the torture to end, I think we can all agree.

There was a big drive to identify what the hell Baphomet was in the nineteenth century as a part of the general uptick in occultism as well as the nationalist drive to find medieval heroes to justify the project of statecraft.[12] It was at this point that the now familiar Baphomet was created, and it includes a goat head and often goat hooves.

But all of these spooky goats aren’t ghosts. And these goats are usually expressly male. They aren’t a ghostly she-goat.

But all of this – the Dürer, and the Baphomet, and even the forced confession of Guillaume Edeline happened years upon years, if not centuries after the Byland Abbey ghost stories were put together. And more importantly all these identification of goats as spooky specifically relate not to ghosts, but to a demoniac understanding. That is not what Snowball was on about.

I find all of this interesting because we just don’t treat animals as ghosts anymore. Medieval people, on the other hand, could and did think of ducks, ravens, and hell even small piles of hay, as ghosts – or at least things that ghosts could appear as – and they found them terrifying.

Why don’t we?

Well, partially we lack the cultural lexicon of biblical meaning that medieval people had. They know all the bible stories off by heart and are thus encouraged to be frightened of the allegorical animals contained therein. But how does that explain ducks and ravens? Or piles of hay? (No I will not shut up about the hay.)

I also think it has something to do with the material realities of medieval culture. Medieval people appear to have imaginations firmly rooted in the world around them. They are around animals all the time, and quite intimately connected to them. This allows them to read animals as scary in a way we currently lack.

Now in the twenty-first century we only really encounter a lot of these animals in circumstances of repose. Ducks are something you see in a pond in a park. I used to see ravens at home in the PNW in the mountains or forest, but now I see them if I go see the semi-tame ones at the Tower of London, or occasionally when I am walking in the countryside. In all these cases those are situations of relaxation. Horses? I mean horses are like a dream pony princess thing, and I see them again while hiking in the countryside. Goats? Babe, it has to be a petting zoo. So, these animals are thus relegated to the leisure part of my brain, is the point. And sure, yeah there are still farms and country folk, but the majority of the world’s population is now urban, and they share this lack of animal access. Hell, if you see horses on a farm these days, they are largely there for pleasure anyway. We don’t need them to pull carts and transport a peck of beans.

I would argue, then, that part of the reason we don’t see animals as frightening or ghostly is partly because we now see them as companions or as linked to relaxation and pleasure. They therefore don’t occur to us as actors in their own right who can end up being ghostly. Here, Wales and its animal ghosts acts as a counterpoint which proves my rule. Those animal ghosts are haunting countryside, where people are still more closely linked to the animals in question.

I think all of this is important, because there is an unfortunate tendency to act as though society has always been the same, and it’s just that we get better tech. The Byland Abbey ghost stories show us social understandings are always in flux. We cannot reliably say that we even find the same things scary that our ancestors did. And that’s a good thing, because it means we can constantly remake meaning.

I dunno, maybe we can bring back the idea that piles of hay are scary. That might be cute.

[1] Delyth Badder and Mark Norman, The Folklore of Wales: Ghosts, (Cardiff: Calon, 2023), p. 71.

[2] A. J. Grant, ‘Twelve Medieval Ghost Stories’, Yorkshire Archaeological Journal 27 (1924), 364.

[3] Ibid., 365.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid., 368

[6] Ibid., 368-369.

[7] Ibid., 372.

[8] Similarly, a ghost horse appears in the tenth story, when a disgruntled lord hires a necromancer to conjure the dead and discover who is stealing his meat. (It’s a ditcher.) The dead man appears first as ‘a serving man with clipped hair’, and then as ‘a very beautiful horse’. (Ibid., 373) The horse follows the ditcher around, spying on him stealing meat, until said ditcher confesses his sins, at which point it is no longer possible for the ghost to see him. I haven’t included this in the larger discussion because the horse is included here expressly to not appear scary. Similarly there is a parade of spirit animals who appear in story eleven, and I can’t decide if they are ghosts themselves or spirits, and this article is already so fucking long man…

[9] Nicholas Jacquier, Flagellum Haereticorum Fascinariorum, ed. Ioannes Myntzenbergius (Frankfurt am Main: N. Bassaeum, 1581), 27.

[10] On the debate, see Zrinka Stahuljak, Pornographic Archaeology: Medicine, Medievalism, and the Invention of the French Nation, (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2012)pp. 71 – 73.

[11] Sean L. Field, “Torture and Confession in the Templar Interrogations at Caen, 28-29 October 1307”, Speculum, 91(2), 304-305. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43883958

[12] See Ibid., pp. 71-98.

For more on medieval ghosts, see:

My fav saints: St Procopius of Sázava, a spooky saint

For more on medieval animals, see:

On cats

On the bull semen explosion

Support the blog by subscribing to the Patreon, from as little as £ 1 per month! It’s the cool thing to do!

My book, The Once And Future Sex: Going Medieval on Women’s Roles in Society, is out now.

© Eleanor Janega, 2025