I was lucky enough to get to see a production of Christopher Marlow’s (1564 – 1593) Edward II at the Royal Shakespeare Company this week, and as with any good piece of art I come across, I have been thinking a lot about it since.

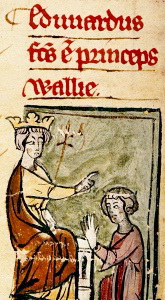

Edward II (1284-1327) is one of those historical figures that people don’t really know what to do with, but Marlowe in the sixteenth century decided to take him on, and wrote a startling and nuanced play about the man and his court.

Why don’t people know what to do with Edward II? Well, cuz he was queer. Like, big time. And it makes people now uncomfortable. Yeah, not then, now.

I’ve talked about Edward tangentially on podcasts before because I am a big fan of his wife Isabella of France (c. 1295-1358), AKA Isabella the She-Wolf (positive). But he is a really interesting character in his own right, in that his entire life and rule are pretty much centered around the fact that he was incredibly stupid about his boyfriends (plural).

The first of said important BFs was Piers Gaveston (c. 1284-1312). Piers was a noble of not particularly notable family, but came into contact with Edward at court and quickly became what is referred to in polite/cowardly circles as Edward’s “favourite”. I am not a coward, or indeed stupid, so I am gonna go ahead and agree with literally everyone around Edward and Piers at the time who maintained that the two were banging big time.

As a result of, you know, all the banging, Piers ended up doing stupid stuff like standing up for Edward in disputes between him and his father Edward I (1239-1307). See Edward II was … not great with money. He liked to spend it, and as a result he was always either beefing with his dad or the court treasurer Walter Langton (d. 1321).[1] The senior Edward got so annoyed with his son about this, that at one point in 1305 he banished Edward II, as well as Gaveston and several other fops and dandies that his son hung out with from court.[2]

But Edward I couldn’t stay mad at these silly little guys, and the following year they were allowed back at court and given knighthoods. Since they were allowed back to court, young Edward decided to ask his dad is Piers could be given the county of Ponthieu in France. The old Edward got super mad about this because, um, no you can’t give our French holdings to your random BF?[3] The older Edward may or may not have grabbed his son by the hair and thrown him out of the room.[4] Then he sent Piers away again. Now is that likely an exaggeration? Yes, absolutely.[5] However, the point is that the whole situation was messy messy.

Piers agreed to go back to Gascony and Edward sent him off in some style, sending him off with £260 in cash, five horses, and two fancy outfits with his coat of arms to wear at tournaments. He also sent an unspecified number of swans and herons, cuz dudes love birds. He then rode down to Dover with Piers accompanied by two minstrels. It was all very lavish.[6]

Anyway, Edward I popped his clogs the following year.[7] Edward II celebrated by immediately recalling Piers and making him the Earl of Cornwall, and presumably going to town on it as well.

But Edward II needed an actual factual queen since that’s how you get heirs, and being a king with an heir is rather the done thing. And he had a great betrothal to Isabella, a French princess, and in 1308 he made good on his promise to marry her.

He went over to France to fetch her and left Piers in charge of England while he was gone, which is again pretty cute.[8] Isabella was only 12 at the time and the entire thing was a big old formality. When you got married to someone that young basically you had the religious ceremony and as a general rule of thumb you would wait to consummate the whole thing until the young person in question was at least sixteen years of age.

This seems to have been fine with Edward who was busy consummating with Piers and also a bunch of other random chicks. He fathered a bastard named Adam during this period, for example, so never let it be said that he didn’t have time for the ladies as well.[9]

However, according to one chronicler writing in the 1320’s Edward might have been being super cute and slutty with it, but Still Piers was his main man, Edward, he claims, that from the first time Edward II saw him he “immediately fell in love with” the Earl of Cornwall “so much that he entered into a firm covenant with him, and bound himself with him before all other mortals with an indissoluble bond of love, firmly drawn up and fastened with a knot.”[10] Cute. Except, um, for all the continuing to give this random dude a bunch of lands and titles and tonnes and tonnes of power. How did some jumped up lad from Gascony control the throne while Edward was away? Who was this dude?

If you are enjoying this post, why not support the blog by subscribing to the Patreon, from as little as £ 1 per month? It keeps the blog going, and you also get extra content. If not, that is chill too.

The Barons, famously a touchy bunch when it comes to land and power, were super unamused. According to the St Paul’s annalist, the trouble was that “two kings [were] reigning in one kingdom, the one in name and the other in deed”. The chronicle the Vita Edward Secundi echoed this, stating that Piers was “a second king.”[11] The Barons would be damned if someone other than them had undue influence over the king.

They threatened revolt. Isabella was mad because Edward was always hanging out with Piers at banquets instead of her, and the French crown threw its weight behind her. The actual Pope was told that Piers was acting up, and he was threatened with excommunication. And that’s how Piers got exiled again.[12]

Edward missed his BF so so much. Yeah, he wanted him to have lots of land and power, but even more he wanted to smooch him (probably), and so he agreed with the Barons that he would limit Gaveston’s power, and that they would get more say in government. The Pope lifted the threat of excommunication, and Piers ran straight back into Edward’s arms.[13]

This time things seemed … OK? Isabella was like “Whatever dude, as long as you don’t give my lands away IDGAF.” The barons were kinda fine. At first. B=But Edward was immediately back to his old ways, and tried to make Piers his military advisor against Scotland. The barons were like “Dude, what did we just say about letting some random have all the money and power?” And Edward was like “IDK what to tell you, this is my kink.”

Anyway, Edward, Piers, and Isabella at one point in time when and fled to safety like a cute little polyam family.[14]

Unfortunately for everyone, the barons got hold of Piers and straight up executed him on 18 June 1312 for treason, saying that he wasn’t upholding the Ordinances of 1311 which Edward had agreed with them, which included “do not let your hot BF be the boss of me.”

This went down badly. The king was super upset about his BF being murdered, as you do. Some of the barons felt kinda bad about the whole kangaroo court and murder thing or whatever.[15] Others were staunch in their belief that you don’t get to override the extant power of the nobility just because you meet a really hot dude. Once again war loomed, but at the eleventh hour a peace was brokered where everyone agreed to go to war with Scotland instead, presumably so the Barons could get a bunch more land and serfs.

Things remained sorta rocky in the kingdom because it was the beginning of the fourteenth century and the Great Famine had broken out. However, as a general rule everyone agreed to be mad at Scottish people instead of each other, and they were all sorta kinda just muddling along.

But then – a new twink appeared.

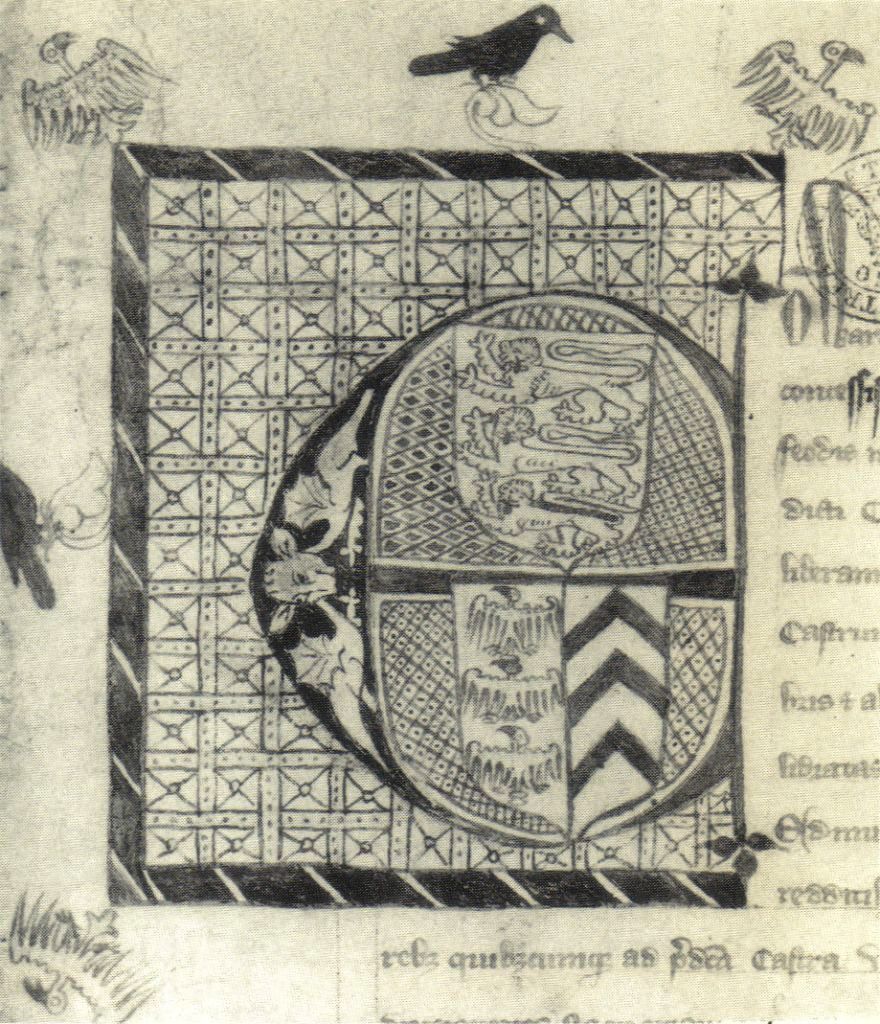

The twink in question was Hugh Despenser (c. 1287-1386). His family were well connected at court and held a bunch of lands in the marches of Wales. Notably, they held a lot of land next to the Earl of Lancaster who was primary amongst those mad at Edward for giving his BF a bunch of power and land at the expense of the other Barons.

Now, at this point it had been almost a decade since the death of Piers. Ten years can make men a bit wiser and more cautious in relationships. Edward II was not of this disposition. He immediately began lavishing lands, titles, and jewels on young Hugh. As Philips notes, the Anonimalle Chronicle records that “The king loved him dearly with all his heart and mind, above all others, so that there was not in the land any great lord who, against sir Hugh’s will, dared to do or say the things he would have liked to have done.”[16] Eventually the entire Despenser family were getting the same treatment. and all hell absolutely broke loose.

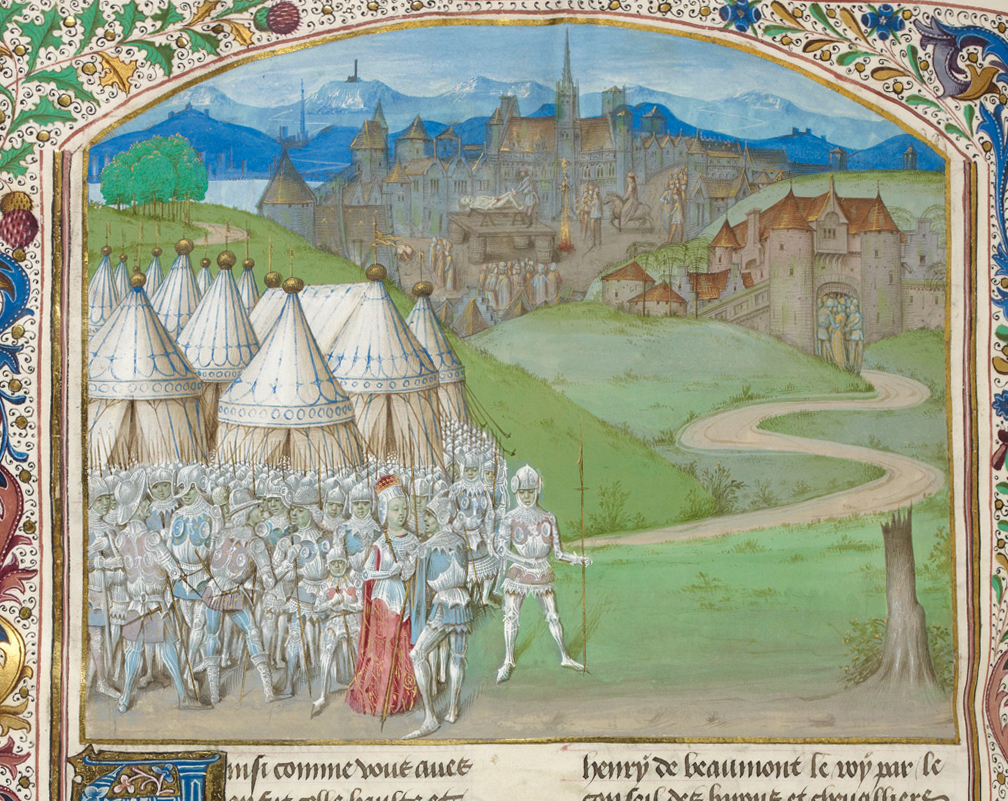

The Marcher Lords declared war. Isabella, who really really did not like Hugh, took off for the French court. There she spent a couple of years marshalling forces, and probably getting together with the exiled Marcher lord Roger Mortimer (1287-1330), and then returned to England with an army. Edward II fled west with Hugh. Hugh was killed. Edward was imprisoned and died somehow. Isabella took the throne in the name of her minor son Edward III sorta kinda alongside Roger Mortimer, and then the two of them took their own turn spending the kingdom’s money on themselves until Edward III took the throne and killed Mortimer. Isabella retired to be a doting mother and grandmother, and was particularly involved with raising the Black Prince.

This is not exactly the way that Marlow portrayed Edward’s downfall. He didn’t get involved with the Despenser Wars part of the equation at all, focusing instead on Piers Gaveston, and never addressing Isabella and Roger Mortimer raising their own armies. The play also implies that Mortimer was killed as soon as Edward II died, which he wasn’t, and that Isabella was also killed, which she absolutely was not. I don’t particularly care about that because it’s a piece of art, and even a super truncated version of the events as they stood has taken me almost two thousand words to write up. So, I get it.

What is important, in my opinion, is that the play does an incredible job of showing what the actual issue with Edward II was – he overstepped his bounds by impoverishing the English nobility in order to spoil his boyfriends (and at times their families as well). That was his issue. Yes, technically you weren’t supposed to go around very publicly being openly queer. In theory. In practice queer people were absolutely being queer all over the shop in medieval Europe. Nuns were having sex and calling each other their little bird.[17] Transwomen were helping each other transition in inns outside of Oxford.[18] And kings were making their boyfriends the Earl of Cornwall.

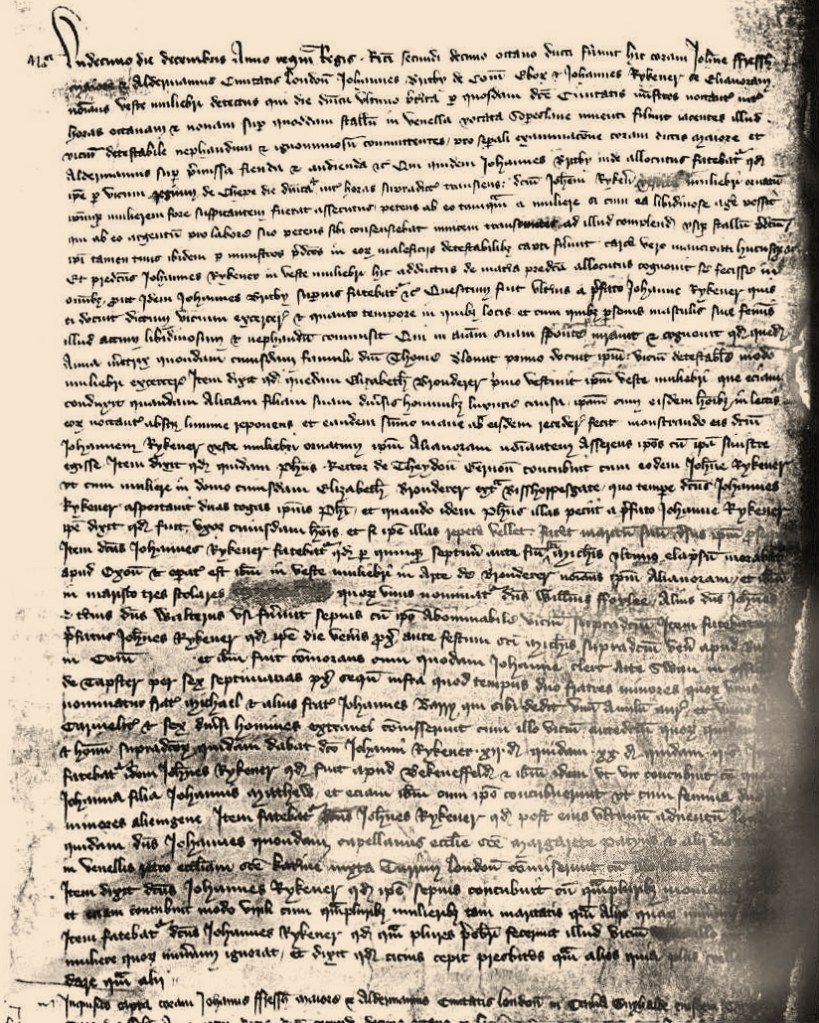

The queerness as a problem thing most usually came up if you then also did something else that you ought not do. I mean, uh, in the case of gay monks and nuns, the issue is you are a member of the clergy and not supposed to be shagging anyone. We know about how the dolls were transing each other because Eleanor Rykner got caught having sex with a john in a site where sex work wasn’t allowed. And Edward’s gayness became a problem when he took money and lands from other lords to enrich his boyfriend’s family.

The play Edward II gets this. It also does a great job of portraying exactly why Edward II would have been so baffled by the reaction of the lords to all his gifting. He was, after all, not necessarily a man but The King. He had undergone a religious transformation at his coronation to become something more than a man. He ruled England and as such he should, to his way of thinking, be able to dispense with its lands (pun intended) to whomever he saw fit. That was his tragedy. He was unable to see why or how he could be challenged if he decided he wanted something.

Indeed, this is the real crux and drama that Marlow got to the heart of – a man baffled by how his kingship could be usurped. And I will tell you what – that is, indeed, highly unusual. You generally don’t go around arresting kings even when they don’t rule particularly well. Ordinarily, to have a fight over a throne you have to press a point of succession issues. This would go on, I would argue, to have lasting ramifications in England, because now suddenly it became clear that you could depose a king here and there if you had a good enough plan in place. That made the whole Wars of the Roses stuff seem a lot more possible.

I would also argue that it is probable that had Edward managed to just quietly have a sidepiece here and there that we wouldn’t have heard very much about it. After all, kings had been having side pieces and even having them celebrated for quite some time. (*cough* Henry II and Rosemund Clifford *cough*) But if you want that to happen, you can’t go around taking lands off your cousins. Indeed, Marlow’s dramatisation from the sixteenth century seems to agree with me on that one. It hinges on the idea that the dukes are pissed because they see themselves as being insulted due to usurpation.

This is important. It’s important to show the past as weird, messy, and, yes, queer. We didn’t invent being gay in the twentieth century, and the past is a lot more complex than a lot of people are willing to acknowledge. Very sadly, we are living through a time where, more than ever in my lifetime, people are angry about the idea that the past was more complex than Baby’s First World History would lead them to believe.

Historical artifacts like Marlowe’s Edward II give us the opportunity to acknowledge the nuance that has always existed in history. If a sixteenth century playwright can get his head around gay relationships in the early fourteenth century, so can you.

I am indebted to the Royal Shakespeare Company for allowing me to come backstage to interview their actors about what I feel is an incredibly important and necessary piece of art, and for inviting me to see the production. If you want to hear more about that you can check out my podcasts about it over at Gone Medieval.

If you have the chance, I encourage you to go see the production. (You can get tickets here.) You’ll be thinking about it for a long time.

[1] Seymour Phillips, Edward II, (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2010), pp. 94-95.

[2] Ibid., p. 107.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Walter of Guisborough, The Chronicle of Walter of Guisborough, ed. Harry Rothwell, 3. Vol. 89, (London: The Camden Society, 1957) 382–383.

[5] For more on this see Phillips, Edward II, p. 120, especially note 249.

[6] Ibid., p. 122.

[7] Michael Prestwich, Edward I, (New Have, CT: Yale University Press, 1997), pp. 556-557.

[8] Phillips, Edward II, p. 133.

[9] Ibid., p. 101.

[10] “Quem filius regis intuens in eum / tan-tum protinus amorem iniecit quod cum eo firmitatis fedus iniit, et pre ceteris morta- /-libus indissolubile dileccionis vinculum secum elegit et firmiter disposuit innodare.” Quoted in George L Haskins, “A Chronicle of the Civil Wars of Edward II.” Speculum 14, no. 1 (1939): 75. https://doi.org/10.2307/2853841.

[11] Phillips, Edward II, pp. 135-136.

[12] Ibid., pp. 147-149

[13] Ibid., p. 160.

[14] Ibid., p. 186-187.

[15] Ibid., p. 191.

[16] Quoted in Ibid., p. 368.

[17] See Jaqueline Murray, “Twice marginal and twice invisible: Lesbians in the Middle Ages”, in, Vern L. Bullough and James A. Brundage (eds), The Handbook of Medieval Sexuality, (New York and London: Garland Publishing, 1996) p. 196.

[18] See, M. W. Bychowski, “The Transgender Turn: Eleanor Rykener Speaks Back”, in Greta LaFleur, Masha Raskolnikov, and Anna Kłosowska (eds), Trans Historical: Gender Plurality before the Modern (Ithaca, NY, 2021; online edn, Cornell Scholarship Online, 19 May 2022), https://doi.org/10.7591/cornell/9781501759086.003.0005. <Accessed 31 Mar. 2025.>

For more on queer stuff in the Middle Ages, see:

That’s not what sodomy is, but OK

On conflating drag (and femininity) with sexuality

Support the blog by subscribing to the Patreon, from as little as £ 1 per month! It’s the cool thing to do!

My book, The Once And Future Sex: Going Medieval on Women’s Roles in Society, is out now.

© Eleanor Janega, 2025