You know those little jokes that centre around a person with a PhD being on a plane, and someone asks for a doctor, and they say they aren’t that kind of doctor but the emergency involves their field of study? I love those. If you don’t know what I am rabbiting on about I mean these:

Cute, right?

Anyway I saw one such example online the other day, but I think it was something about African textiles or something? IDK it was cute and funny and I had a sensible chuckle, and then, dear readers, then I scrolled down into the comments (by accident!) and saw something very silly indeed, which ruined it all for me. I didn’t take a screen shot of it, but basically the world’s most dull person was compelled to respond to said cute little joke by saying, ‘Don’t call yourself doctor then.’

Now, this is not the first time I have encountered such a sentiment. Very occasionally weirdo right wing people will attempt to rile me up by saying ‘I’m not going to call you doctor because you’re not an MD’ to me online. Which, like OK cool, I’m going to continue to never consider anything about you. You have fun.

What those weirdos have in common with the person yelling at a meme is this: they are being pretty confidently and loudly wrong, and today we are going to talk about why.

See the thing about the term ‘doctor’ is that for a long long (long long long long long) time it meant pretty exclusively people with PhDs.

It’s a nice and fun medieval thing because, well, so are universities. Universities were invented in Europe in the twelfth century as a convenient way to get annoying people to go yell at each other somewhere other than the local cathedral.

By this I mean, of course, that education over the medieval period had several stages. In the early medieval period, a great deal of philosophical and theoretical learning and education was centred in monasteries. During the Carolingian Renaissance, our good friend Charlemagne spent rather a lot of time and money making sure that this would continue, but also attracting people to court in order to nerd out. From there we then also had the rise of cathedral schools. See, to be in the Church you had to be literate, by which I mean you had to read and write in Latin. And if you were going to participate in the higher echelons of its legal structures you needed fancy Latin. So the place to go for that was a cathedral where people were already being high fallutin’ and had climbed the ranks of the Church so they knew what was needed to make that happen.

Universities came about in several different way from there. The very first university was at Bologna and it was started essentially by a student union. A bunch of nerds decided that they wanted more specialist education and did a call out for instructors who came to the city and would dole it out. Next came Paris, now the Sorbonne, which was much more of an instructor-led approach. A lot of the biggest names in philosophy descended on the city and made it known they would be taking pupils, establishing the universitas magistrorum and scholarium Parisiensis. Then you got Oxford, where basically a lot of people who had been at Paris drifted back to England and eventually King Henry III (1207-1272) gave them a royal charter to try to convince everyone that England was fancy.

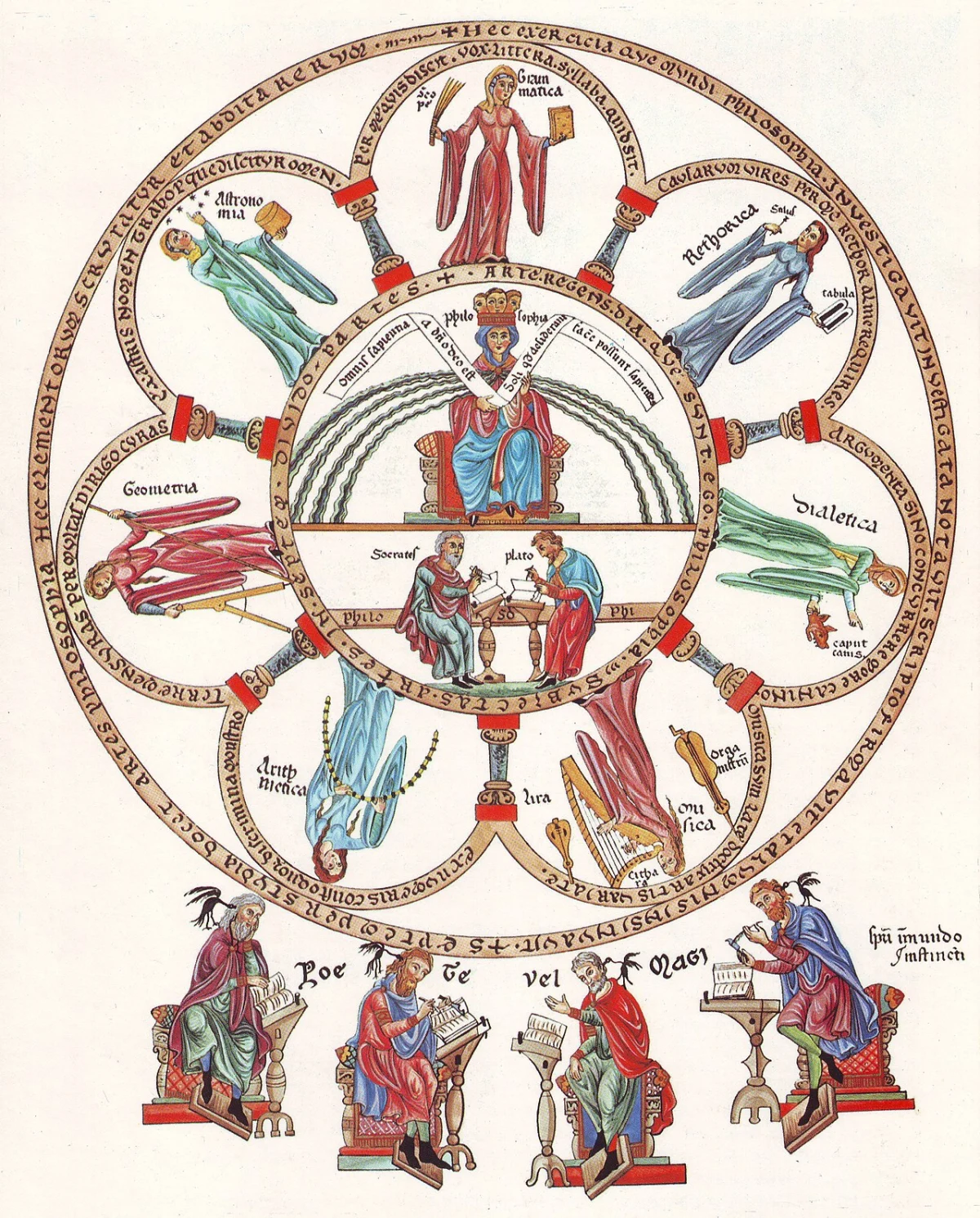

No matter how they were founded, the universities all taught the same thing and awarded the same degrees based on the liberal arts curriculum. In this system, the first thing you had to master was the trivium of grammar, logic, and rhetoric. This was essentially three ways of dealing with the world in Latin. Grammar just means Latin, logic meant reading a bunch of classical history (in Latin) and then trying to argue like Plato or whatever. Rhetoric meant yelling at each other in Latin. I am being serious.

If you are enjoying this post, why not support the blog by subscribing to the Patreon, from as little as £ 1 per month? It keeps the blog going, and you also get extra content. If not, that is chill too.

Anyway, if you got good enough at being totally insufferable in varying Latin was then congratulations – you received your Bachelor of Arts, or BA. As a general rule of thumb this took around three or four years. From here, you could either go take up a literate job at court or in the Church or you could continue your studies. That meant that you had to move to what were known as the higher faculties of a university where you would begin to learn to the quadrivium or arithmetic, geometry, music, and astronomy. Completing these four subjects could take up to twelve years, and at the end you would be a Master of Arts and be awarded a doctorate, because the two things were synonymous.[1] This is the very first way to use the term doctor.

OK but say you are a sick individual, such as myself, and you wished to torture yourself yet further with learning? Well you can do that! There were further degrees which could be taken in law, medicine, or theology. And you know what the most important one of these was? Theology. These faculties were tightly controlled and could only be found at Paris, Oxford, Cambridge, and Rome until my boy Charles IV started up one of my almae matres the University of Prague in 1374.[2] (It’s called Charles University now. Shout out!) Legal degrees could also be conferred at all of these places. In either case you would be known as a Doctor of Theology, or a Doctor of Law. Pretty cool.Similarly you could also train to be a doctor of medicine and get a degree saying that you were such a thing – and there were specialty schools like Salerno where people went to do just that.

However, the term “doctor” wasn’t usually used to speak about those who subsequently went on to work with patients in the field of medicine. Why? Well, the term “doctor” comes from the Latin verb “docere” meaning to teach. So, if you were called a medical doctor it meant that you were teaching at Salerno, not that you were out in the field actually doing the stuff you were trained to do.

The people who got trained at Salerno, took their degree, and went out into the world to practice medicine needed a title which made it clear that they were not university professors, but university trained, so that people knew what their job was. And they had one – they were called physicians.

The term here comes, again, from Latin physicus which means things that relate to nature. In Old French and English this is then adopted as fisicien and physic, respectively, and in the thirteenth century we begin to see the Anglo-Norman word “physician” crop up. The word here is important because it was a means by which such men (and they were overwhelmingly men because women were often precluded from attending university because one had to take holy orders to do so) differentiated themselves from all of the other types of medical practitioners out in the world.

There were midwives who saw to pregnancy, birth, and well actually quite a lot of other medical issues if you lived in rural places where it would be difficult to thrive as a professional medical provider just due to population density. In cities it was easier to find other people to treat you as well. There were master surgeons, who were trained to, you know, cut you up and take things out by means of apprenticeship.[3] From 1308 onwards the Barber Surgeons were then established as guilds and you would go to them if you wanted some bleeding, or to treat minor wounds, or get your hair cut, and they soon overtook the Master Surgeons as the guys for all your cutting based needs.[4] There were also apothecaries, who were sort of like what we call chemists in the UK or pharmacists in America, who dispensed medicines.[5] In places like England, you needed all of these people to provide medical care because university-trained physicians were much more likely to be found where there were rich people that you could charge for your well-trained expertise.

Physicians were also much more likely to be found in places where there was a university training people up, like, say, in the Italian lands. But the Italian lands were weird because since Salerno was there, the universities would often oversee all sorts of medical practitioners, including midwives to make sure everyone was working as they should.[6] Because of this even places like Florence, which didn’t always have a university would have guilds which oversaw everyone.[7] The Italians were special like that though, so don’t go looking for this type of coverage in, say, rural Scotland.

All of this is to say that there were a lot of different ways to receive medical treatment in the medieval period – and a lot of different ways to address the people you were receiving them from – but none of those had a salutation of “doctor”.

In English the term “doctor” didn’t start being used to address people with medical degrees until the seventeenth century, and it began more particularly in Scotland. Funnily, the use of the term was meant to confirm respect to the doctor confirming that, yes, they were very smart indeed. Yes, that’s right – they were as smart as all the people with PhDs, bless them.[8] The medical people were trying to catch up with the humanities people because everyone knew that it’s really hard to get a PhD and it confers authority. This took off because everyone post-enlightenment absolutely loves to crank themselves about how important Science is, or whatever. The fact remains however, that it is a relatively new occurrence.

Here in the UK there is also resistance to the flattening of medical knowledge under the term “doctor”. Here, for example, it is a point of pride with surgeons that the retain the titles Mr/Miss/Ms/Mrs as appropriate. I think that is super cool.

The point of all this is that it is a historical fact that the term “doctor” is supposed to refer to people who have a PhD and teach, and we let medical practitioners start using it cuz we are not weirdo gate keepers. If you wanted to be a dick about it – which I do not – it technically makes more sense to prevent medical doctors from using the term because they have a professional degree, not a formal doctorate. So anyone trying to make some sort of point about the whole thing is simply wrong, and also annoying.

So to close out let’s try our hand at a medieval version of the joke we started with. If you said “doctor” to people in the middle ages, they would assume that you were talking about the doctors of the Church because it was just the common understanding. For medieval people, then, the version of the doctor joke would be being on, say, a boat to Rome, when someone calls for a doctor on board. The Physician trained at Salerno with a medical degree would then say, “Oh no there must be a misunderstanding, I can’t help.” Then the people would say, “This woman’s humors are unbalanced!” So the physician says, “I’m here.” Yes, they are technically a doctor (if they also finished their trivium and quadrivium before their medical training), but it’s just not what anyone was thinking about.

Trust me. It’s hilarious.

[1] A great overview on all of this, if you want to go further, is Olaf Pederson, The First Universities: Studium Generale and the Origins of the University Education in Europe, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997).

[2] Walter Rüegg, Asa Brigg, Geschichte der Universität in Europa 1: Mittelalter, (München: Beck, 1993), p. 33.

[3] Vern L. Bullough, ‘Training of the Nonuniversity-Educated Medical Practitioners in the Later Middle Ages’, Journal of the History of Medicine, 14 (1959), p. 447.

[4] Carole Rawcliffe, Medicine & society in later medieval England (Stroud: Alan Sutton: 1995), p. 218.

[5] H. Rolleston, ‘The Historical Relations of Pharmacy and Physic’, The Pharmaceutical Journal 139 (1937).

[6] Bullough, ‘Training of the Nonuniversity-Educated Medical Practitioners’, p. 446.

[7] Carole Rawcliffe, Urban Bodies: Communal Health in Late Medieval English Towns and Cities, (Woodbridge: Boydell and Brewer, 2013), p. 294.

[8] AA Asfour, JP. Winter, ‘Whom should we really call a “doctor”?’, Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2018 May 28;190(21):E660. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.69212. PMID: 29807940; PMCID: PMC5973890.

For more on medicine and myths about the medieval period, see:

On medical milestones, being racist, and textbooks, Part 1

On medical milestones, the myth of progress, and textbooks, Part 2

For more on medieval education, see:

Podcast alert: a medieval education

Support the blog by subscribing to the Patreon, from as little as £ 1 per month! It’s the cool thing to do!

My book, The Once And Future Sex: Going Medieval on Women’s Roles in Society, is out now.

© Eleanor Janega, 2024

This seems a little bit sanitised as a history of doctors. Where did the more negative meanings of the verb ‘to doctor’ come from, then?

LikeLike

That connotation appears in the eighteenth century, only in English, and you would have to say that also we see cooks negatively because we also “cook the books” for example, so I don’t know what you are getting at here.

LikeLike

Sure, but… in the modern era, the one we’re actually in now, “doctor” sans other context is by default meant to mean an MD. Identifying oneself as a doctor today (especially in a context where someone is asking for “a doctor”) is universally understood to mean a medical doctor.

Knowing the historical details is interesting (I didn’t know a lot of this before reading the post), but it’s not going to make me think that someone asking “Is there a doctor here?” might be looking for a Ph.D. Nor do I think it would be an improvement if it did; emergencies that require quickly identifying a medical professional far outnumber all other kinds of emergencies, and stopping to clarify whether you’re “that kind of doctor” would not be helpful in any way.

LikeLike

Not really. But OK. ❤

LikeLiked by 2 people

Could you elaborate a bit on the part about “Master surgeons” and “Barber surgeons” ?

I’ve never read anything about that and I’m not sure that I understand what you mean either.

LikeLike

If it wasn’t for the word physician, I would argue it was due to English being inadequate for precise communication. Could we teach the Americans in particular to use it?

In German and in the Scandinavian languages there are commonly used words (dk Læge comes from healer) that does not refer to the academic degree.

LikeLike