Unfortunately, though I have made the world’s best booty shorts and deployed them with great skill and aplomb, there are still those in our society who refuse to heed my message, and also to learn basic history.

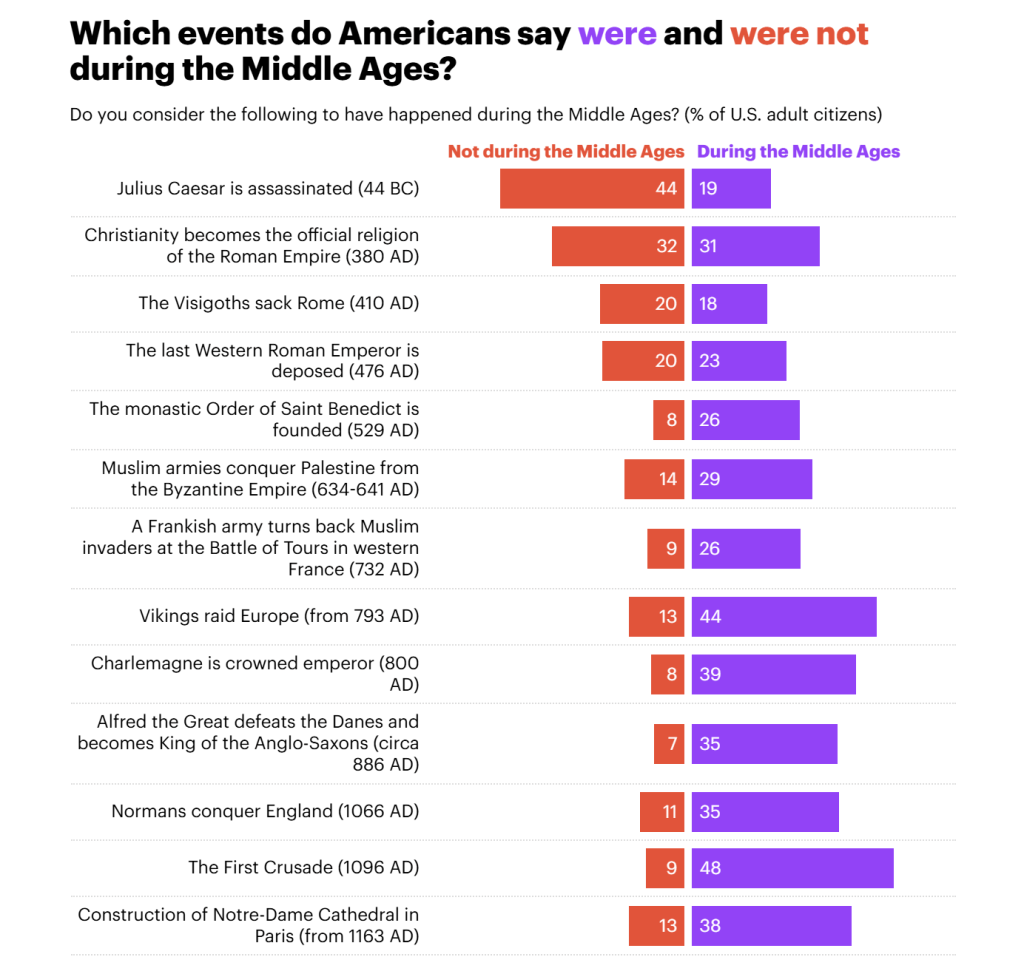

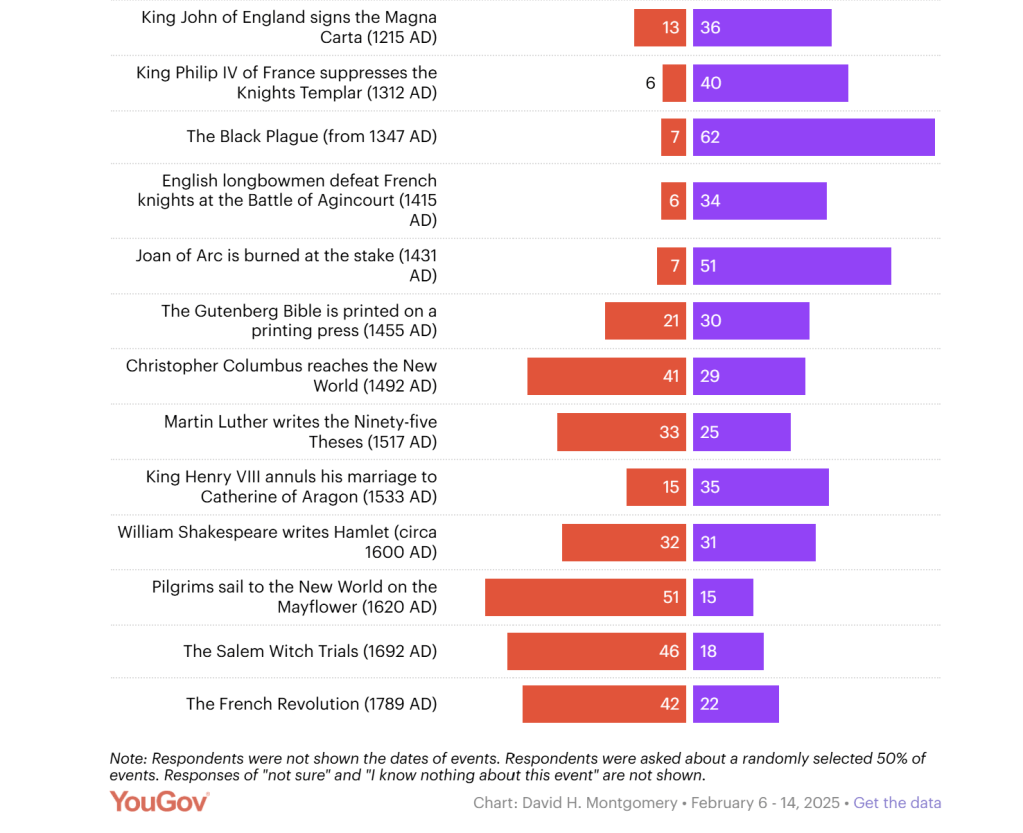

This fact was brought to my attention once again this past month when a terrible take floated across my serene feed over at bsky.app (which, incidentally is the place you are most likely to find your girl posting of late). In this case the terrible history in question was this:

Read more: On contrarian history

Fun fact: this man then blocked me when I made fun of him for being woefully ignorant on the subject and suggesting he should probably not try to opine on things when he hasn’t done the reading. Because of course he did.

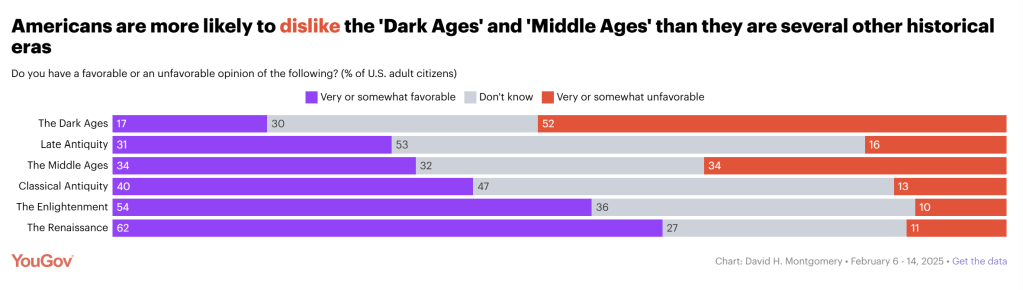

Of course, I know you are not an ignorant blowhard, and indeed, because you are here, I assume I hardly need to relitigate the fact that the term Dark Ages does not refer to a period of intellectual or cultural decline. You are all aware that it simply refers to a time of limited source survival. And you all also understand source survival and how it works.

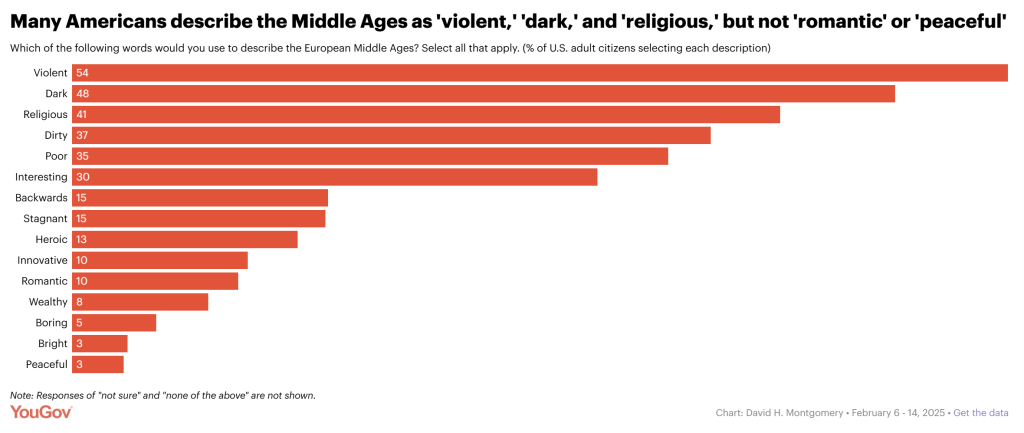

What is interesting to me here in this take, other than the continued and wilful ignorance of individuals who wish to see themselves as better than medieval people, is that this view is only possible if we don’t consider the material conditions of average people.

Because of how source survival works, or indeed, how architectural survival works, we are often encouraged to think of the past as a place populated entirely by the wealthy elite. After all, it is the wealthy elite who write the majority of historical sources, in that they are often the only people trained to be literate. This is by design in order to create an elite population, of course. This tactic will persist into the modern era with, for example, forced illiteracy on enslaved populations.[1]

Further, it is elites who have the ability to preserve documents. You need libraries to keep documents safe, and those are expensive and difficult to keep from burning down. The sort of person who has that kind of ready cash will ensure that the documents preserved are those which show them and their ancestors in the best possible light, and which reinforce their own cultural and economic control of the society. So you mainly just hear about rich people and what they owned as well as a lot of justifications for why you can’t be mad at them for resource hoarding. It’s quite dull.

If we are thinking about buildings, the same is also true with some added factors. Most ordinary people’s houses, especially in Europe, were made out of organic materials. There’s rather a lot of building with wood and/or wattle and daub going on. This cannot survive for millennia. What can survive is things that were made out of stone. This privileges the survival of things like monumental architecture (such as the colosseum in Rome, for example), or religious architecture (temples, churches, and cathedrals) and the homes of the wealthy. From a Roman standpoint the homes of the wealthy are, for example, villae.

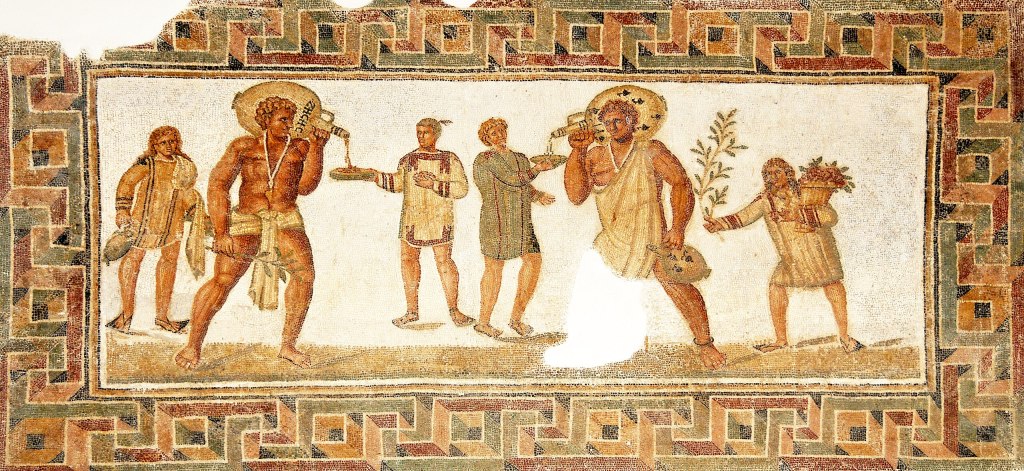

Much is made of said villae. ‘Romans had underfloor heating! Roman houses were decorated with beautiful mosaics!; Now, technically both of those statements are true – but you need to ask yourself which Romans enjoyed those things, and how it was that they managed to do so. The answer is a violent, crushing, and brutal slave empire.

Every Roman villa where we find the owners enjoyed underfloor heating was actually kept warm by the enslaved people keeping the system’s fires going. Sometimes, the beautiful mosaics include images of enslaved people being beaten. The lavish lifestyles that the people inside enjoyed were made possible by brutally controlling the local population of wherever they had reached, and forcibly taking their goods and sometimes just the people themselves. But we don’t get to hear from the people doing all the actual work around here very often, because of their position in society.

And lest anyone attempt to convince you that all of those workers were just happy to be part of the giant violent slave empire, I very much encourage such parties to read the excellent Strike: Labor, Unions, and Resistance in the Roman Empire by Sarah E. Bond, which is full of examples where workers attempted to band together to argue for better conditions and pay. These are not the actions of people who are happy with their lot.

If you are enjoying this post, why not support the blog by subscribing to the Patreon, from as little as £ 1 per month? It keeps the blog going, and you also get extra content. If not, that is chill too.

Further, anyone who would argue that actually it’s great being enslaved is encourage to consider if it would be great for them personally. Because here is the thing – if you go back in time to the Roman Empire you are not going to be a senator. You will be a peasant. Further, if you went back in time to say, Pergamon in the first century CE, then according to Galen (c. 129 – c. 216), there’s about a twenty-five percent chance that you would be enslaved.[2] If we keep in mind that in general we think enslaved populations decline in the late antique period, depending on when and where you are born, some estimates about enslaved people in the Roman Empire go as high as forty percent of the population being enslaved. I, personally, do not believe that is good, cute, or worth it so that twelve guys can have really cool mosaics in their dining rooms.

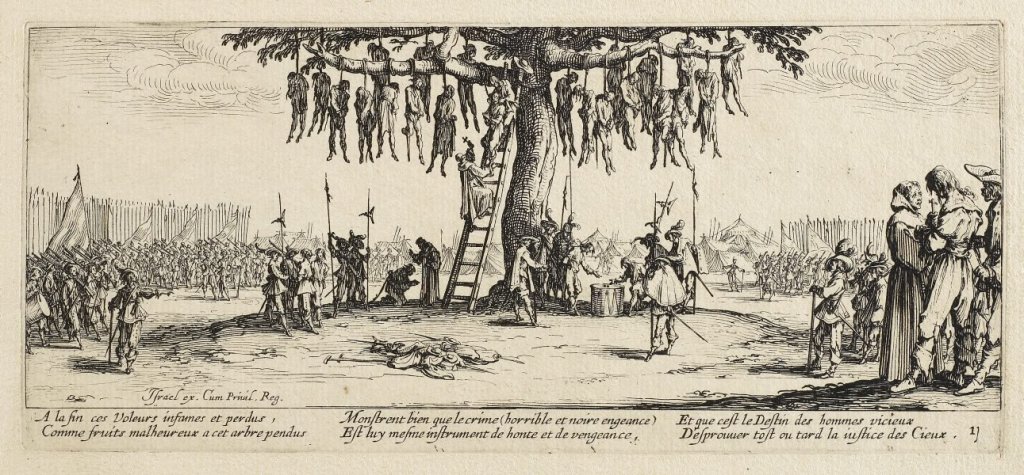

To be fair to Romans (though why I should be is anyone’s guess) there are some good things that Roman rule provided via taxes – roads, for example. And sure, Roman cities did indeed look pretty cool, and I am pro-city as a general rule. However some of the things that your taxes would pay for – like ampitheatres – are just bad. I do not think it is cool to make enslaved people fight each other to the death. I do not think you should import exotic animals and then slaughter them before a crowd.

Again, those who would defend these practices are encouraged to consider whether they would volunteer to be a prisoner of war ritualistically slaughtered before a crowd, or whether they think of themselves as the Emperor enjoying the spectacle. I think it is important to think about which scenario is more likely.

At any rate, all of this – the spectacle of conspicuous consumption, the violent games – is neither here nor there when we begin to speak of the collapse of the Western Roman Empire and the transformation of Europe in the early medieval period. Because here is the thing – yes I do think that it is good and also cool when slave empires collapse. Because then they can’t do wholesale enslavement. That’s one thing.

The other reason it is good? Because the collapse of said Empire doesn’t actually mean that there is a collapse in industry, and in fact is usually linked to increased life expectancy in local communities.

Case in point – post-Roman Britain. There has been some really interesting archaeological research in this area of late, and one thing they have found is that after the Romans fuck back off to the continent, things like metal production actually increase in volume. Yes there was an eventual crash in that production in the sixth century, but that happens because everyone got the Justinian plague.[3] Even if you like Empires because you are a weird sicko, I am afraid you have to admit that they do not, in fact, somehow curtail the spread of plague in a world without germ theory and antibiotics. The Roman Empire, therefore, is actually not necessary for keeping industry going.

Further, analysis of the skeletons of people in Britain after the Romans left shows us that their health improved quite a bit. As a general rule this is seen as consistent with a more balanced diet and increased calorie intake. Over time this leads to an increase in height as well as a longer life span.[4]

Considering these factors – who is eating what, what is being made, who is consuming it – is at the heart of understanding history. You will never be able to convince me that the society that starved a native population so a couple of rich guys could have a fancy house and go watch prisoners of war be killed for sport is better than the one that sees the average person become healthier and live a longer life. I do not care if those rich people were enjoying goods imported to the region from North Africa. Those rich people were a vanishingly rare segment of the population and their consumption patterns were only made possible through horrible crushing violence perpetuated on average people.

And here’s the thing, that is not ‘contrarian’ that is called ‘historical analysis’ which is done by ‘historians’ when we do things like ‘analyse primary sources’ and archaeologists when they ‘dig up bones’. That is what we do. That is the work. Further, the fact that there is no such thing as a ‘Dark Ages’ and that a term we used for source survival has escaped containment and been rendered meaningless by a bunch of poorly read self-congratulatory dolts is, in fact, what we call ‘settled academic fact’. This isn’t a debate! That is literally what is true!

Of course, there is at the heart of this sad man’s idiotic rant the standard irony: he is arguing that the ‘Fall of Rome’ crated a ‘Dark Ages’ which was bad and is a term that is pejorative from a place of total ignorance. This man has never read an actual history book. He knows nothing about the early medieval period. If I asked him to describe the system of governance in Visigothic Iberia, for example, he is unlikely to even understand what I am asking. Yet he has a deeply held opinion on this era which he chooses to put about online. And he will block medieval historians such as myself if we take offence to his positioning us as contrarian.

It is contrarian to argue in defence of a system which steals from workers to give to a vanishingly small segment of a wealthy population. It is contrarian to refuse to learn about a subject and still think your opinions on it are valid. It is contrarian to ignore experts when they correct your profound and deep-seated misunderstanding.

However this man, and the legions of those who will go to bat for a violent and oppressive Empire, do not see themselves as contrarian because they are not engaging with actual history, they are engaging with a hegemonic historiography. They believe in the glory of the Roman Empire and its inherent good because they themselves currently live inside a violent empire that exists to funnel money to a wealthy elite. If you begin to question whether Rome was bad for the average person – if you start to ask why there was money for some people to have underfloor heating, while there wasn’t enough to adequately feed the population of Brittania – you may start asking questions about what is happening around you.

There is no such thing as revisionist history. Writing history is a constant process of re-evaluation of sources and attempts to control for the biases of the past as well as our own. Anyone who calls the people doing that work contrarian, or accuses them of attempting to ‘rewrite history’, fundamentally doesn’t understand what history is and what it does. Or perhaps they do, and they want to prevent historians from questioning the world around us. So, take your pick: are you ignorant, or just a bad person? I can’t answer that for you.

[1] Cornelius, Janet. ‘”We Slipped and Learned to Read:” Slave Accounts of the Literacy Process, 1830-1865’, Phylon (1960-) 44, no. 3 (1983): 171–86. https://doi.org/10.2307/274930.

[2] Ramsay MacMullen, ‘Late Roman Slavery’, Historia: Zeitschrift Für Alte Geschichte, vol. 36, no. 3, 1987, pp. 365.

[3] CP Loveluck, MJ Millett, S Chenery, et al., ‘Aldboroughand the metals economy of northern England, c. AD 345–1700: a new post-Roman narrative’, Antiquity. 2025;99(407):1320-1340. doi:10.15184/aqy.2025.10175

[4] Alvaro Luis Arce¸ Health in Southern and Eastern England: A Perspective on the Early Medieval Period, PhD Thesis, University of Durham, 2007. https://etheses.dur.ac.uk/2595/ <Accessed 24 November 2025>

For more on myths about the medieval period and empire, see:

There’s not such thing as the Dark Ages, but OK

I wasn’t taught medieval history so it isn’t important is not a real argument, but OK

On successor states and websites

On colonialism, imperialism, and ignoring medieval history

Support the blog by subscribing to the Patreon, from as little as £ 1 per month! It’s the cool thing to do!

My book, The Once And Future Sex: Going Medieval on Women’s Roles in Society, is out now.

© Eleanor Janega, 2025